Aethelred’s punch-drunk tenure resulted in the English Kingship passing for the first time into Danish hands. Fortunately, the Viking leader Canute (1017-1035), was a just and able ruler, wholly devoid of ego, who treated all his subjects, Danish or English, with fairness and impartiality. He was succeeded by his sons – Harold Harefoot (1035-40) and Hardicanute (1040-42). But these were men of lesser stature, and their reigns made no impression. The Danish royal line expired with Hardicanute, so the Witan – the Anglo-Saxon parliament – invited Aethelred’s last surviving son, Edward, to accept the crown.

Edward had been sent to Normandy for his safety as a boy and he had stayed there ever since. He brought a coterie of Normans with him – courtiers, chaplains, counsellors – to advise him in matters of policy. This went down poorly with England’s leading men, especially Godwin, Earl of Wessex, who tested the King’s patience repeatedly until Edward banished him in 1051. One year later, however, Godwin and his sons returned with men and arms to spare, and Edward was forced to acknowledge the limits of his power. Godwin died in 1053 and it was his eldest son, Harold, who reaped the rewards of his defiance. From then on Edward abandoned attempts at statecraft and focused instead on what he was best suited for – a life of prayer and contemplation – symbolised by the construction of a new cathedral, Westminster Abbey, and made manifest every day in the King’s unique ability to heal a plethora of mental and physical ailments.

Affairs of state were left in the hands of Harold Godwinson. He put down a joint revolt of the Welsh and Mercians with ease and showed that he would brook no favouritism by reprimanding his brother Tostig, the Earl of Northumbria, for poor governance, eventually sending him into exile in 1065. Harold had no familial link with the House of Wessex, yet when the childless Edward died in January 1066, he seemed the obvious choice to take over. The presence of overseas claimants – William of Normandy, Harald Haardrada of Norway, and Sweyn of Denmark – made it imperative that a strong, effective warlord controlled the reins of power.

It was clear to Harold that Duke William presented the most pressing threat. William was fuelled in his ambition by a belief that he had been cheated out of the throne. Harold, he claimed, had sworn an oath guaranteeing him the crown, and Edward, he said, had long ago promised him the crown. William gathered a powerful army and fleet but was unable to sail as the wind blew against him through the spring and summer. Harold was highly frustrated, as he had top-class, potent forces straining at the leash. But summer rolled on and their thoughts began to turn to the harvest so Harold reluctantly let them depart, trusting that the Normans would not risk a campaign so late in the year.

Then, in mid-September, word came that Harald Haardrada, along with the renegade Tostig, had landed with the Viking host and was ravaging Northumbria. Harold reassembled his army and marched north at breakneck speed. At Stamford Bridge on September 25th, the Norsemen were swept aside and Tostig and Haardrada both killed. Then, while the King was giving thanks, the wind changed in the Channel and the Normans set sail.

Harold was incensed when he learned that William had landed in Sussex. The thought of foreign invaders trampling over English soil disgusted him. His brothers advised him to bide his time, but Harold had only one gear – forward – and he ordered his troops to march back south at full pace once again.

Many of his soldiers were unable to keep up. Harold arrived at Senlac Hill, near Hastings, on October 13th with just over half his army. Again, his brothers urged caution. Reinforcements were nigh, they counselled, but Harold had passed the point of being able to listen. He was a man no more but a point of sheer flame – a human burning bush – blazing with zeal for the love of his land. A nimbus of glory shone out around him, and his brothers shielded his eyes as he turned and walked away.

The next day at sunrise Harold planted his standard – The Fighting Man – deep into the ground. He stood atop the hill like a Saxon Herakles, his men clapping and cheering behind him, stripped to the waist, beating his chest, and bellowing down to the Normans below.

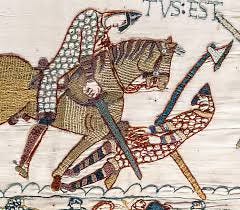

So William gave battle, wave after wave of cavalry crashing pointlessly into the Saxon shield wall. After three hours, he had nothing to show save piles of Norman dead. But over-excitement on the part of the English turned the tide of the struggle his way. The sight of a few Normans fleeing down the hill in disarray proved too tempting for some. Groups of giddy troops rushed after the foe and were cut to pieces at the bottom of the slope by William’s reserve. Now, for the first time, there were holes in the wall. So William chipped away at the English line and through a series of calibrated charges and feigned retreats made slow but steady progress.

Evening drew on and William, aware of nearby reinforcements, ordered his archers to fire directly into the Saxon ranks. An arrow pierced Harold in the eye, and the shield wall wavered with shock and partially dissolved. Norman horsemen flooded the gaps, surrounding the Saxons, who were fighting back to back now in increasingly isolated knots.

Even then, with one eye useless and half his face hanging off, Harold was still sure that he would win. He had never tasted defeat before and did not know what it was like. But then he was slain, and the Fighting Man was ripped out of the ground. His brothers and chief men were killed with him, and when the reinforcements arrived there was no-one left to lead them. Night came down on the Anglo-Saxon era, and the English people passed for the first time into servitude.

You're the best history teacher I've ever had! I love this series, thanks John!