Over the water in Ireland, on the banks of the Shannon, not far from Lough Derg, a son was born in 941 to Queen Be Bhionn of the Dal Cais clan. The Dalcassians lived in the district of Thomond, just north of the mighty province of Munster. This infant – Brian Boru – was the twelfth son sired by the tribe's king, Cennéting mac Lorcain. As such, he was not expected to ascend to the throne. It was assumed that he would join the priesthood, so he was sent away to study at a nearby monastery. Here Brian had a rich and varied education, learning Latin and Greek, memorising the careers of Caesar and Charlemagne, and analysing the military and geopolitical strategy behind the Greco-Persian wars.

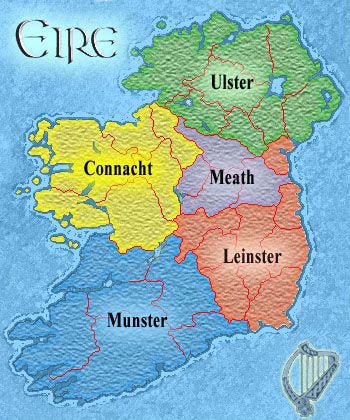

Ireland, at this time, was divided into five proud and independent provinces. In language, culture and religion, the country formed a unified whole, but there was no overarching political settlement to draw the bickering kings and sub-kings (151 in total) along one constructive path. Boundaries frequently shifted, but the territorial layout generally corresponded to Ulster in the North, Connacht in the West, Meath in the centre, Leinster in the East, and Munster in the South. Pacts of convenience were made and unmade as kingdoms and tribes squabbled over land and prestige. Ireland was like early Anglo-Saxon England in this respect, but with one major difference. The Kingdom of Meath belonged exclusively to the High King of All Ireland. From the reign of Arthur to that of Alfred, there had been no equivalent figure in England. In days of old the Irish High King had sat upon the Hill of Tara and ruled the whole land. But his power had become diminished, and his role had been reduced by Brian’s time to that of political ringmaster – holding the balance and ensuring that none of the other four provinces grew overly strong. This lack of a central, commanding authority made it easy for the Vikings to establish a series of coastal bases at Waterford, Wexford, Limerick, Cork, and especially Dublin, which became an immense and ever-expanding bastion of Norse puissance.

Brian’s studies came to a brutal end in 952 when a Viking raid on the royal palisade took the lives of his father and many of his siblings. Mathgamain, his brother, became king, and Brian returned to work alongside him in political and military matters. Three years later, a similar raid saw his mother and other family members slaughtered. The horror of these events left a life-long mark on Brian. His hearth and home had been violated by Danish savagery. Such acts of butchery could not be tolerated in his precious homeland, and the only way to guarantee peace and order, he came to believe, was through national unity and a single, dominant ruler. Like Julius Caesar in the last days of the Roman Republic, he saw that the political system he had inherited had no answers to the demands of the time and needed to be sloughed off like an old and used up skin.

Mathgamain and Brian took ownership of Munster in 964 when they captured the Rock of Cashel, the seat of the ruling Gaelic family. After Mathgamain was killed, Brian expanded into Connacht and Leinster and engaged in a decades-long battle of wills with the reigning High King, Máel Sechnaill II.

By 1002, Brian’s Sword and Sun banner flew over all five Irish provinces. Through force of personality, a crystal-clear purpose, and knowing when to attack and when to defend, Brian succeeded in imposing his vision on both the quarrelsome natives and the obdurate Vikings. He made everyday Irish folk part of his achievements, giving them something to build and aspire to that transcended their petty egos and small-scale grievances. He brought them grandeur and a collective self-belief that had not been seen or felt for centuries.

Something big was stirring. Ireland was fast becoming a civilisational powerhouse. Brian still had to put down a number of rebellions in Ulster, but by 1010 his rule appeared absolute and he began to be known as the Emperor of the Gaels. He invested heavily in the country’s infrastructure – both spiritual and material – churches, monasteries, schools, hospitals, roads, and bridges. He had plans for a centralised system of command and a standing army that could guarantee Ireland’s security for the millennium to come. He transformed his homeland into a mini-Imperium and the realm stood on the brink of lasting, substantial glory when evil played its final card.

The Gaels of Leinster joined with the Dublin Vikings and declared war on Brian, demanding independence from his rule. Brian gathered his troops and the armies met in a bloody, day-long battle at Clontarf, just outside Dublin, on Good Friday 1014.

Evening drew on and Brian’s men broke the enemy line and chased the Northmen and renegade Irish into the sea, where the waves foamed red with their blood. But triumph turned instantly to lamentation, for right at the end of the battle Brian was killed in his pavilion by an opportunistic Viking. His son and heir-apparent, Murchad, was also slain in the last minutes of the fighting after having dispatched a hundred opponents throughout the day.

Brian’s designs were thus blown clean apart. The vision of unity was shattered, and the kings and sub-kings returned to short-term thinking and fratricidal strife. The Vikings were never a force again after Clontarf, but Brian had known that there were other powers on the rise, closer to home than Scandinavia, who could potentially make their presence felt. England, for instance, had been a unified, cohesive state since Alfred’s day. The Anglo-Saxon kings were not expansionist by nature and had troubles of their own keeping the Danes in check. But what if the Saxons were one day overthrown, not by the Vikings – a deadly, but known and somewhat disorderly quantity – but by an efficient, high functioning body politic with self-perpetuating, self-generating territorial aims?

What then for Ireland? What then?