In the last piece I wrote in this series, back in May, I reflected on the eternal value of The Aeneid and the story of Aeneas’s recovery and triumph from the ruins of Troy to the foundations of Rome. But it was easier for Aeneas in some respects than it is for us today, trying as we are to navigate a contemporary scene full of confusion and discordance. Aeneas already knew what his mission and purpose in life was before he set out. His mother, the goddess Venus, told him exactly what he needed to do and where he needed to go and Aeneas was able to use this as a springboard to create facts on the ground. Though he veered from his path at times and was laid low by misfortune and temptation, he always had that North Star to pull him back and set him on the straight and narrow again.

T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets - Burnt Norton (1936), East Coker (1940), The Dry Salvages (1941) and Little Gidding (1942) – though written nearly two thousand years later, in a sense comes before The Aeneid in that it gives us orientation and gets our inner compass working. It’s a voyage to a beginning. Because if we don’t know who we are or where we’re going, we’re not going to get anywhere at all. It’ll be ever decreasing circles all the way down.

What’s important, what’s really crucial, is what Eliot names ‘the still point’ – a centre of calm certitude at the heart of each one of us and also at the heart of the cosmos – the opposite of fragmentation, a place of unity and coherence. ‘The still point of the turning world’, he calls it.

But how to get there from where we are now? That’s the hard part. That’s where we need to take a good long look at ourselves. What do we see there? Many sins and failings and wrong-turnings, no doubt. Maybe worse. We have to acknowledge all that, feel the weight and futility of it, accept it, offer it up, and step forward in faith and love. We are who we are and we are where we are and we have to take that as our base camp.

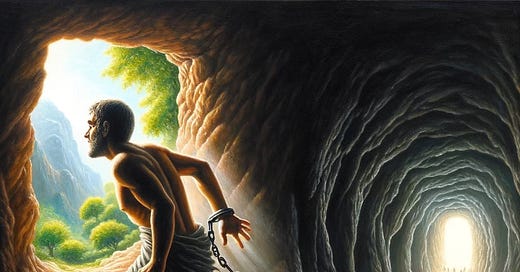

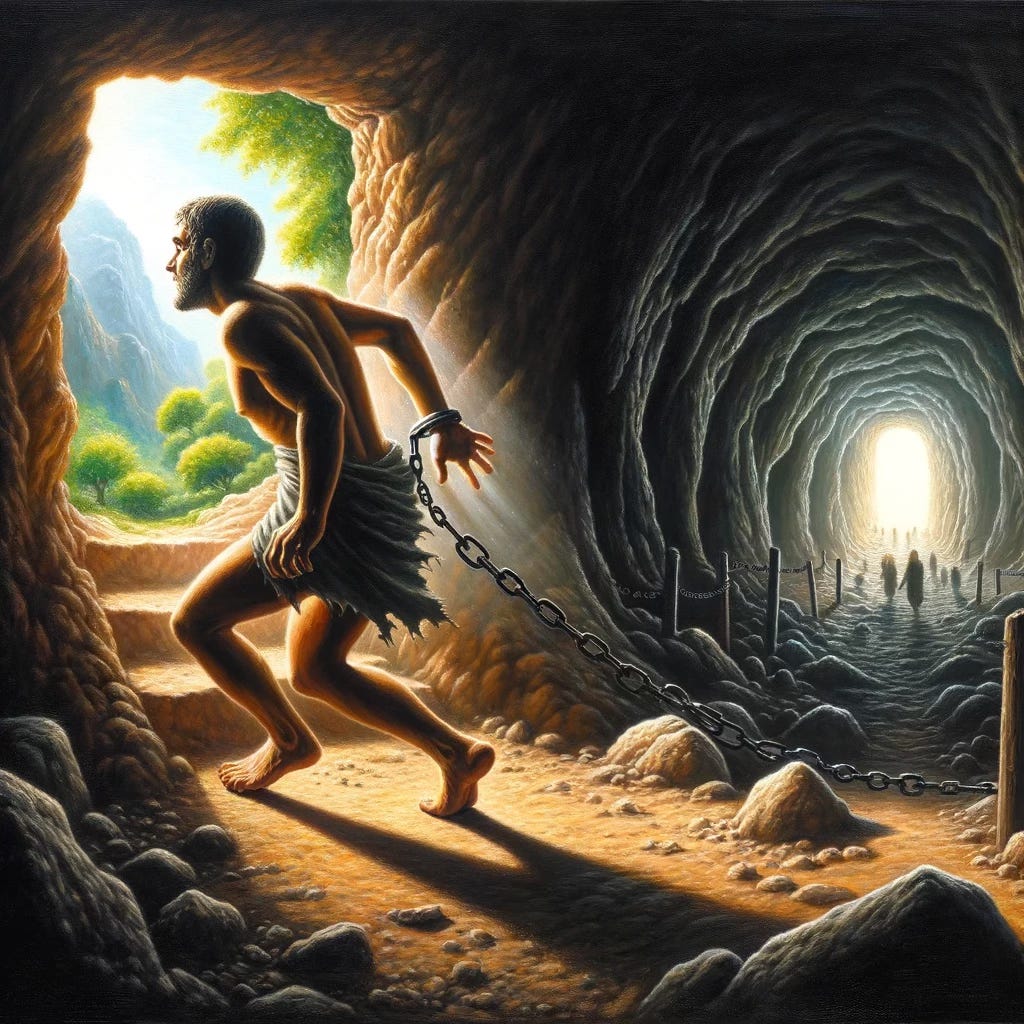

The way up is the way down; the way out is the way through. As he tells us in Little Gidding, we can only be ‘redeemed from fire by fire.’ Sometimes we’re so far lost and so deeply asleep that we can only be scorched back into life; burnt back into Being. This is the confrontation with the Self – the Dweller on the Threshold – and it costs nothing less than everything.

What happens next then? Once the débris is cleared away? This is where we start putting building blocks for the future in place by asking ourselves a series of rigourous but constructive questions: Who am I really? Not as my ego would like me to be or how the ‘great and the good’ would like me to be but who I actually, truly am. What did I like doing as a child? Could I do that again now? What is my deepest desire? What am I all about? What do I stand for? What do I care about? To what extent have I ever become ‘the real me’? Do I even know who that is? To what extent has that person been swamped and silenced by the dictates of society? How do I slough off all the false selves I have accrued over the years? Where do I come from? Who are my ancestors? What did they believe in? What, if anything, did they fight and die for and how does that apply to me now? Who are my people, historically speaking? What part do I play in the continuum between time past, time present and time future?

‘History is now and England’, Eliot declares in Little Gidding. In other words, where you are now and right this very moment. This is where things start to happen, what he calls ‘the point of intersection of the timeless with time.’ A space has been made, a clearing created for grace and goodness to enter our lives.

This is where the good stuff begins. In Dantean terms, we have crawled out of Hell and clambered up Mount Purgatory and are now ready for lift off into Paradise, into a world full of pattern, significance, purpose and value. We have divested ourselves of so many harmful accretions and so many layers of falsity and are now facing the right way round, towards the Sun. Whatever the outer circumstances, there is something unshakeable in us now. It’s a platform to greatness. We have left the illusions of Plato’s Cave behind and are surging forth towards the light and the stillness and the dancing. That’s where the music is and that’s where you are too, here and in eternity.

It’s a lifetime’s work, in truth, reading and reflecting on Four Quartets. But give it just three months – a few lines every day – and you will see a difference, I promise you. It’ll take you from whatever state you’re in now – relatively content maybe, or mired in passivity/mediocrity, or just a total smashed up mess – ‘a heap of broken images’ as TSE says in The Wasteland. It’ll take you from there and bring you closer – so that you can touch it, taste it and smell it – to the power and glory and splendour of who you really are, of who you were made to be, of who you will inevitably become now that the gunk has been cleared and you are pointing the right way. In this world and the next. Now and forever. Where ‘all is always now.’

Ok, I appreciate it. Thanks again John 👍

Great post - but did you know that quoting so

Much of Eliot’s work is illegal and the copyright holders are incredibly fierce to take action against you….?