It seemed that at any moment one was going to be able to walk right through the screen of surface appearances, as through a mirror, into a strangely violent but exalted world of poetry and revolution.

David Gascoyne, Collected Journals, 1936-42.

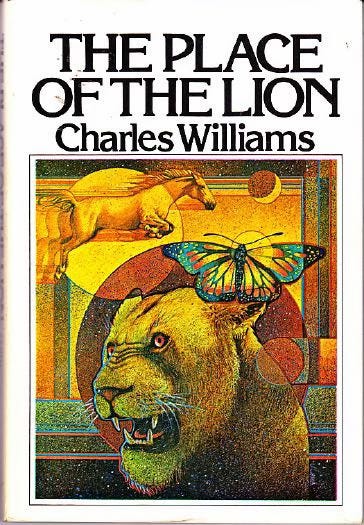

The Place of the Lion contains little in the way of characterisation and psychological depth. It is not that kind of book. But this is by no means to suggest that Charles Williams's fourth novel (published in 1932) is in any way a shallow or trivial read. Quite the reverse. It is a 'novel of ideas', certainly, but also a carefully crafted work of art about the power and reality of ideas themselves. It is about ideas in a way that most modern literature, with its tendency to foreground human emotion and sensibility is not. It deals with ideas in the raw.

Viewed from another angle, however, one could equally build a case that the human condition is central to the text's concerns. The story explores, in sixteen tightly-knit chapters, the turn events might take were angelic intelligences to burst through from the archetypal realm and start disrupting the safe, predictable world human beings have fashioned to keep them at bay. How men and women react to this rupture - how deeply and sympathetically we respond to these presences - is always going to be key:

‘You're doing what Marcellus warned you against,’ Richardson said, ‘judging them by English pictures. All nightgowns and body and a kind of flacculent sweetness. As in cemeteries, with broken bits of marble. These are the principles of the tiger and the volcano and the flaming suns of space.’

What results, as the narrative unfolds, is nothing less than the collapse, re-imagination and re-integration of an entire world.

This clash of levels (plus ensuing discordance) occurs more frequently, if less dramatically, in our daily lives than we might think. Illness, bereavement, redundancy, any kind of trauma or emergency or - conversely - experiences of joy, love, harmony and connection, can strip us of our egoic defences and open us up to what reality is like at deeper, more essential levels.

The moral of the novel might be for us to try and remember (though it's hard to think straight when worlds collide) not to batten down hatches, curl in on ourselves and drift aimlessly with the flow. Better to dig deep, kindle our specifically human qualities - integrity, faith, creativity - and map these onto the world as best as we can and in concert with others, as Damaris, Anthony and Richardson are compelled to do in the book.

'Human kind cannot bear very much reality,' wrote T.S. Eliot in Burnt Norton. He was right. It bites. But, as Williams shows, here and elsewhere, that need not be a bad thing.

‘You'll never be comfortable,’ says Anthony to Damaris. ‘But you may well be glorious.’