All across the Empire, not just in Britain, faith in Christ waxed over the next two centuries while belief in the old gods waned. Emperors lost confidence in Heaven and placed their trust in men instead, boosting the military and thinking to gain security thereby, now that the High Powers that had raised Rome from city-state to world-empire were losing substance and tangibility.

Septimius Severus (193-211) began this trend, and when the Emperor Alexander was killed by mutinous troops in 235, a chaotic three and a half decades ensued, with a revolving door of soldier-emperors striving for supremacy and all sense of order and direction gone. Far from the strife, in Egypt and in Sicily, Saint Anthony the Great and Plotinus the Philosopher explored heights and depths of contemplation which would help build, in time, the world to come after the final fall of Rome. The spirit of the age – volatile, disturbing, uncertain – pushed them beyond the limits of the Greco-Roman mindset. For it was the God behind the gods, the God beyond the rise and fall of Empires, who was calling them upwards and on.

But anarchy ran wild from the cities to the borderlands and back again and calamity followed calamity in a catastrophic, despair-inducing parade. The Emperor Decius was killed in battle in 251, and no Emperor had died like this before. Worse came in 260 when Valerian was captured by the Persians and used as a footstool by their Emperor, Shapur I, until he was flayed to death and his skin stuffed with straw and hung up as a trophy. The Empire split into three – West, Middle and East – and all seemed lost until Aurelian (270-275) - the Restitutor Orbis – World Restorer – made the broken Imperium one again.

Many territories, throughout this time, had endured the scourge of barbarian attack. In Britain it was Saxons from northern Germany who would land by night, plunder a villa or a farmstead, then disappear across the sea before the depleted patrols could catch them. During the reign of Diocletian (284-305), that most capable and organised of men, the decision was made to augment and enhance the British fleet - the Classis Britannica - to face down this Germanic threat. Carausius, a sea-captain of humble birth and high ability, was named commander. He succeeded mightily in his task, but it began to be noised about that he was keeping the pirates’ loot for himself rather than returning it to its owners or donating it to the Imperial Treasury.

So the authorities stripped him of his office, but Carausius did not submit. He knew – and Rome knew – that he ruled the waves and that the Classis Britannica made him invincible. So he withdrew to Britain and assumed the purple and there was nothing the other Emperors in Rome and the East could do but accept him as their equal. Carausius reigned from 286 to 293 and proved himself a far-sighted and popular ruler. He was the first British leader to recognise how vital sea power was for future security and success. He also showed that political independence did not necessarily mean burning bridges with the wider Roman polity. In this sense, the country had the best of both worlds – sovereign, but not separate or cut off. He made it plain to his successors that Britain could flourish and excel as a unified realm with just one man – as in the days of Brutus and Brân the Blessed - at the helm.

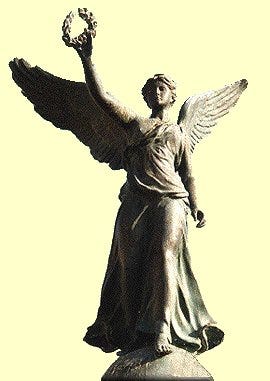

But the aura that now shone around Carausius attracted the cravings of baser men. In 293 he was assassinated by his finance minister, Allectus, who shamelessly usurped his Imperial title. Where Carausius had been generous and broad-minded, Allectus was petty, vindictive and tyrannical, relying on Frankish mercenaries to keep the Romano-British populace down. So when the Emperor Constantius landed with an army in 296, the people rose up to support his attempt to bring Britain fully back into the Roman fold. He defeated and killed Allectus, but the usurper’s barbarian troops took refuge in London where they set about ransacking the buildings and violating the population. But they were crushed by a wing of Constantius’s fleet, sailing up the Thames into the city, and he was welcomed with triumphal garlands by the people and given the title Redditor Lucis Aeternae – Restorer of the Eternal Light.

Constantius came, whether he consciously knew it or not, in the name of the God behind the gods. On the most baseline of levels, his victory signified nothing more than the triumph of one general over another in the interminable civil wars of the period. In terms of politics and society – the next stage up – it signalled the full return of Britain to the administrative life of the Empire. But on the plane of ideas and eternal truth – the same depths and heights that Anthony and Plotinus were wrestling with – it stood for so much more. The Londoners were right. They had witnessed a restoration. But it was an annunciation as well. A prophecy and declaration of intent. The light of European civilisation was back in Britain and a link had been remade with the sacred wellsprings that had irrigated and inspired that civilisation at the source. And that light only burned brighter and stronger and became more potent and revelatory – more world-shaking too – during the reign of Constantius’s son and successor, Constantine the Great.