The prophet breathes the air of freedom. He smothers in the hardened world about him, but in his own spiritual world he breathes freely. He always visions a free spiritual world and awaits its penetration into this stifling world.

Nikolai Berdyaev, Freedom and the Spirit (1927)

Every word in Elidor is freighted with gold. Published sixty years ago in 1965, Alan Garner's third novel does for Manchester what The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960) and Moon of Gomrath (1963) did for the valleys, woods and hills of Cheshire. He imbues the cityscape with a numinous depth charge. The stuff of everyday urban life - lamp posts, railway bridges, terraced houses - takes on an almost sacramental glow. Levels of reality segue into each other. As here:

Roland ran along the wider streets until his eyes were used to the dark. The moon had risen, and the glow of the city lightened the sky. He twisted down alleyways, running blindly, through crossroads, over bombed sites, and along the streets again. Roland stopped and listened. There was only the noise of the city, a low, constant rumble that was like silence.

He was in the demolition area. Roof skeletons made broken patterns against the sky. Roland searched for a place that would be safe to climb, and found a staircase on the exposed inner wall of a house. He sat on the top in the moonlight. It was freezing hard. Roofs and cobbles sparkled. The cold began to ache into him. He wondered if the others had decided to stay in one place and wait until he came.

This thought bothered him, and he was still trying to make up his mind when the unicorn appeared at the end of the street. His mane flowed like a river in the moon: the point of the horn drew fire from the stars. Roland shivered with the effort of looking. He wanted to fix every detail in his mind for ever, so that no matter what else happened there would always be this.

Who can forget writing like this? No-one in my experience. I've never known a book, at least among my circle of friends, which retains its impact for so long in the reader's imagination. People can recall whole scenes. Either that or specific images - e.g. the fiddler in the slum clearance area - leap into their minds as soon as the book is mentioned. Garner's story, in this respect, has much in common with Andrei Tarkovsky's 1979 film Stalker, another quest for meaning through a magical but treacherous landscape. Tarkovsky calls his liminal space the 'Zone', and Elidor has two such 'Zones' - both wastelands; sites of blight and dereliction - the parallel world of Elidor itself and a mid-1960s Manchester which bears absolutely no resemblance to the 'swinging sixties' of popular imagination.

Malebron, Elidor's 'king in exile', disguises himself as a fiddler to lure the Watson children into his world through the portal of a North Manchester church on the brink of demolition. Once there, the children encounter a pre-industrial mirror image of their home city - the bitter legacy of moral and spiritual decline:

‘The darkness grew,’ said Malebron. ‘It is always there. We did not watch, and the power of night closed on Elidor. We had so much of ease that we did not mark the signs - a crop blighted, a spring failed, a man killed. Then it was too late - war and siege, and betrayal, and the dying of the light.’

The children are charged with rescuing the four Treasures of Elidor - a spear, a sword, a stone, and a bowl - from within the sinister Mound of Vandwy. Their next task is to take the Treasures back to Manchester and guard them until Malebron sends word. The difficulty is that there are clearly other powers at work in Elidor than Malebron, determined to seize the Treasures for their own ends. Their attempts to break into the genteel suburban milieu created by the Watsons' parents form the substance of the second half of the book.

For Roland, the youngest and most sensitive of the children, this is a particularly heavy burden. He is greatly impressed by Elidor and more in sympathy with Malebron than any of his siblings. Malebron's goodness and Elidor's physical reality mean everything to him. When his brothers, Nicholas and David, attempt to rationalise what happened in the church, Roland is uncompromising in his defence of Elidor's veracity:

‘What does Nick say, then? That there's no such place as Elidor, and we dreamed it?’

‘In a way,’ said David.

‘He's off his head.’

‘No, he's gone into it more than any of us," said David. ‘And he's been reading books. He says it could all have been what he calls 'mass hallucination', perhaps something to do with the shock after the church nearly fell on us. He says it does happen.’

‘If you can believe that, you can believe in the Treasures,’ said Roland.

Roland is a prophet, and he shares in the eternal lot of prophets - sidelined, patronised, and seen as little more, even by his mother, than a temperamental, overly-wrought schoolboy:

‘You mustn't let your imagination run away with you. You're too highly strung, that's your trouble. You'll make yourself ill if you're not careful.’

The consensus among my friends is that Roland does indeed make himself ill and that, by the end of the book, he is close to 'cracking up.’ I'm not so sure. Roland's only mistake, as far as I can tell is to confuse Elidor - a parallel world to our own and nothing more - with Heaven itself. It is an error which comes from a good place, born out of Roland's great capacity for spiritual insight. It is exactly this ability to see what her brothers and sister cannot see that guides Lucy Pevensie to Aslan before them in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe and Prince Caspian. It is worth bearing in mind as well that participating in the final two chapters of Elidor would be an intense experience for anyone, let alone one so finely tuned as Roland. Nonetheless, I don't find anything in the text to suggest that he can't recover, go on to fulfil his potential and live a life of value and meaning. I take encouragement from Malebron's commendation after Roland has succeeded where his brothers and sister fail in the Mound of Vanwy: ‘Remember, I have said the worlds are linked ... and what you have done here will be reflected in some way, at some time, in your world.’

Roland is a lantern bearer. He unfurls the banner of the Imagination, in both Elidor and Manchester, at the points where disenchantment and desacralisation seem strongest. I also see in him a herald of the coming spiritual resurgence, the Age of the Holy Spirit prophecied by Joachim de Flore in the twelfth century and Nikolai Berdyaev in the twentieth. Roland stands in the High Places, watching and waiting for the signs of this imaginative rebirth. The impact made by Elidor these last sixty years serves as sign and symbol enough, perhaps, that the greening of the wasteland - the recharging and resacralisation of our imaginations - might be nearer than we think.

We will know the day when it comes. Like Elidor, it will be freighted with gold:

Roland could never remember whether he saw it, or whether it was a picture in his mind, but as he strained to pierce the haze, his vision seemed to narrow and to draw the castle towards him. It shone as if the stones had soaked in light, as if stone could be amber. People were moving on the walls: metal glinted. Then clouds drifted over.

Roland was back on the hill-top, but that spark in the mist across the plain had driven away the exhaustion, the hopelessness. It was the voice outside the keep; it was a tear of the sun.

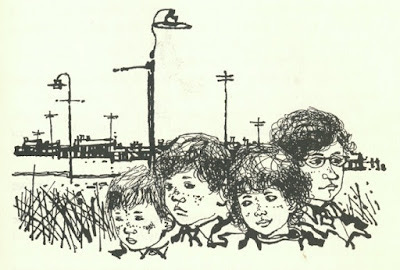

* The illustrations for Elidor were drawn by Charles Keeping (1924-1988), who also illustrated many of Rosemary Sutcliff's children's stories set in late-Roman and early Anglo-Saxon England, such as The Silver Branch, The Lantern Bearers and Dawn Wind. This provides a nice link, I feel, between one era of 'decline' and another. The front cover illustration reproduced at the top of the piece is from the early 1980s (the edition I had as a boy) and by Stephen Lavis.

** The edition of Elidor I have used in this essay was published by HarperCollins Children's Books in 2008, in the Essential Modern Classics imprint.

*** This is an edited version of an essay I originally published on the Albion Awakening blog in January 2017. Please also see a more recent, in-depth exposition here on Substack from August 2022.

Great piece. I started reading it to my daughter tonight after reading this post. She's 11, about the age I was when I read it. She really liked it and wants to hear more so that's good. Thanks John!

Wonderful piece, thank you. The one from 2022 also.

I was not fortunate enough to have read such authors a Alan Garner as a child, as a father of 5 now, I am, however, experiencing the joy of introducing such authors to my children and myself at the same time.