In Wales, they remembered the old ways. More than that, they rejoiced in them. Following Arthur’s death and the diminution of British rule across the land, the Romano-Britons migrated west to the mountains and valleys of Cymru – difficult terrain for the Angles and Saxons, still newcomers to British topography, to penetrate and settle.

Here they established a number of kingdoms linked by language, culture, and a shared reverence for the deep things of the past. Britain’s Trojan origins and the stories of Brutus and Aeneas were celebrated as the life-giving roots of British history. This was a world which Arthur and the Caesars would have known and recognised – the last living bastion of the old Western Empire.

Unlike in Ireland, there was no High King over and above the individual rulers. The opportunity existed, therefore, for a successful leader to shine brighter than his peers and make himself de facto overlord. Gruffudd-ap-Llewylyn (1039-1063) is the chief example, the closest the Welsh have come to emulating Brian Boru. But such pre-eminence made the English king, Edward the Confessor, nervous, and Gruffudd was accordingly hunted down and killed by Harold Godwinson.

The Anglo-Saxon kings had no desire to conquer Wales, but they did have an interest in keeping it divided so as to maintain their dominant position on the island. This relatively stable status quo was turned on its head with the advent of the Normans, born expansionists and specialists in colonisation. As early as 1067 they were making inroads into South and Mid-Wales, sequestering property and parcelling out great chunks of land among themselves.

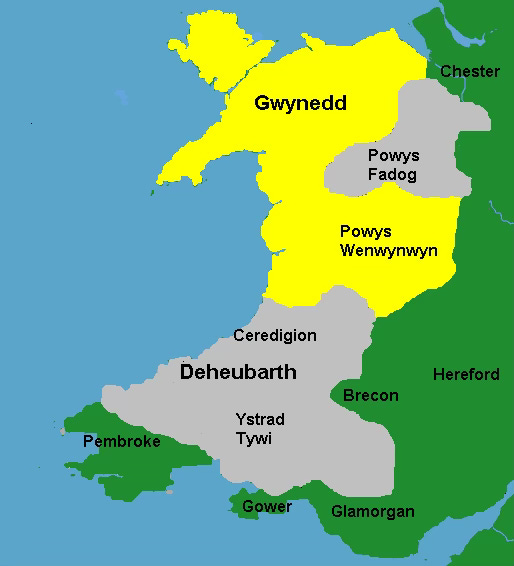

Llewylyn the Great (1194–1240) raged mightily against this arrogance, fighting like a tiger from his Gwynedd lair to push the Normans back and retake most of Wales. In the map below, Llewelyn’s territories are in yellow, those of his client princes in grey, and the remaining Norman lands in green.

But after Llewylyn’s death, King Henry III (1216–1272) repossessed his conquests so that when his grandson, also called Llewylyn, came to power in 1246 all he could call his own was the isle of Anglesey and half of Gwynedd.

Llewylyn-ap-Gruffud was a warrior and a statesman, brave and bold when the need arose but canny and shrewd when required. For three and a half decades he played cat and mouse with Henry and his successor, Edward Longshanks (1272-1307). His vocation, he believed, was to purge the land – all of the land – of the foreign pestilence. But the Anglo-Norman behemoth was disciplined and organised, and there was only so much that a single leader, no matter how gifted, could realistically achieve.

For many years the conflict would remain frozen then suddenly blaze out into open war. Sometimes the natives would have the advantage, sometimes the occupiers. But by 1282, King Edward had had his fill of this stubborn, bullish rival. Edward was a dynamic, hugely ambitious monarch, who saw it as his life’s work to physically own the entirety of Britain. So in the summer of that year he launched a three-pronged attack on Wales, taking personal charge of the northernmost force that sought by both land and sea to starve and blockade Llewylyn into submission.

Edward was a skiful, patient general, who played his cards to telling effect. Trapped in Snowdonia and encircled by the foe, Llewylyn knew that he had to try something unorthodox or face guaranteed defeat. He was also aware that the Welsh to the south were being beaten black and blue by the other English armies. So he gathered a detachment of men and penetrated the enemy lines via secret paths and hidden tunnels. He rushed south to aid his countrymen but was seized upon and slain in a Powys wood in a chance encounter with English troops.

It was a bathetic and underwhelming way for such a great visionary and patriot to die. A grand act of sacrilege then ensued, which cries out to this day to Heaven for vengeance. The soldiers cut off Llewylyn’s head and in a bestial parody of Brân the Blessed’s final journey, marched with it in triumph to London. Rather than bury and honour the head, as the Seven Survivors of the Irish War had done with Brân’s, they hoisted it on a pole, fashioned a mock crown of ivy, and paraded it as a trophy. The stinking mob jeered and hooted and pelted the regal head with rotten eggs and tomatoes. But Susanna, the raving London seer, stood on top of Ludgate Hill, tore her tawny hair and prophecied the blood-spattered end of Norman hegemony and the coming of a second Aeneas to restore the Trojan line.

No-one listened; no-one cared. The Londoners were themselves no longer – not the same people who had thronged the streets for Constantius Caesar and the return of the Roman Light a thousand years before. The dark spell of colonisation had blinded their eyes, blocked their ears, and fouled their spirits to such an extent that Susanna might as well have been addressing them in Gaelic.

King Edward laughed and went on his way, constructing a ring of mighty castles to keep the hardy men of Gwynedd penned in around the Mount of Snowdon. But the Welsh did not hear – as the building work went on – the sound of walls being lifted up. They heard instead and once again the fall and desolation of Troy, her spires and towers crumbling perpetually into the formless void. The last remaining province of the Empire had finally been lost to the barbarians.

And Edward was glad. He named his own son Prince of Wales, then turned his attention to Scotland – to Hadrian’s Wall and the fierce, hostile lands that lay beyond.

Haunting image of Susanna warning the jeering crowd. The roots of the 'dark spell of colonisation' go deep. There are two Britains and its like the two dragons fighting under the castle, one red, and one white. Except the coloniser dragon seems completely triumphant. Would love to see how this plays out into the 'golden age' of British rationalism, Empire, Masonry, and Globalism, and then look forward to the return of the once and future king to revivify the wasteland of modern Britain.