Rosemary Sutcliff (1920-1992) was a prolific storyteller and arguably the finest writer of historical fiction for children that Britain has produced, though her contemporaries Henry Treece and Geoffrey Trease provide stiff competition. For a short, perceptive overview of her oeuvre, please see here. There is a distinctive note which rings out in all her writing. Sutcliff herself summarises it well in her preface to The Light Beyond the Forest (1979):

The medieval Christian story is shot through with shadows of half-light and haunting echoes of much older things; scraps of the mystery religions which the legions carried from end to end of the Roman Empire; above all a mass of Celtic myth and folklore … In reading this book try to remember, as I have done all the time I was writing it, the shadows and the half-lights and the echoes behind. 1

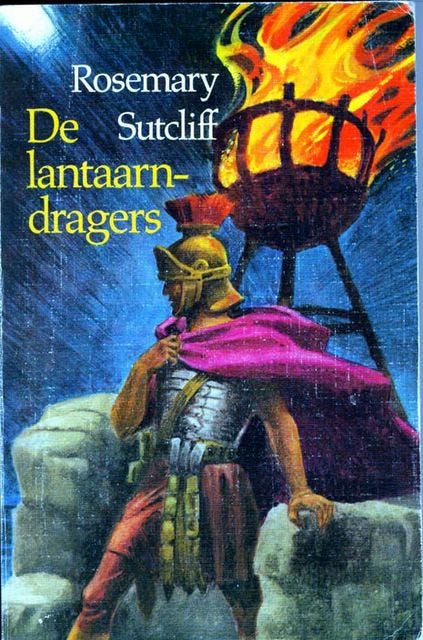

Shadows, half-lights, echoes. The novel we are considering here - The Lantern Bearers (1959) - is charged with this half-hidden extra dimension from first page to last. It recounts the fall of Roman Britain and the eclipse of four hundred years of civilisation and stability - its collapse into anarchy and bloodshed, before a partial restoration of the old Roman pattern, a triumph that could signify the last hurrah of a dying order or the foundation of a new, unforseen dispensation. The future is left open. The struggle remains uphill, but everything is still there to play for.

The Lantern Bearers won the prestigious Carnegie Medal for childrens' writing in 1959. The recipient of the same award three years before had been C.S. Lewis's The Last Battle. The two books share a common theme - the end of one world and the beginning of another, and how individuals and societies respond when familiar political, cultural and religious landmarks are either taken away (The Lantern Bearers) or inverted (The Last Battle.)

Lewis's story is a macro-apocalypse - the consummation of the age - the End Times followed by Christ's return as King and Judge and the descent of the Heavenly City (see Matthew 24 and Apocalypse 21/22.) The Lantern Bearers, in contrast, is a micro-apocalypse, the end of a world rather than the end of the world. In a full-scale apocalypse, time comes to a stop and eternity takes over. The sun and the moon (the old order) are darkened and give way to an entirely new mode of living and being. This is what happens in The Last Battle. In the mini-apocalypse of The Lantern Bearers everything crashes into ruin around the protagonist, Aquila, but night follows day and day follows night and the story moves on, both on the macro and the micro scales. Aquila, in a sense, has the worst of all worlds. As a young and proud Romano-Briton, everything that had given his life value and significance has vanished, yet there is no grand eschatological dénouement to bail him out. Time has not yet hit the buffers. Somehow he has to find a way forward and through.

Could this be a good thing? Might we even suggest that Aquila enjoys the best of all worlds - alive and whole (just about) but with all prior bonds broken? While this is undeniably distressing from a human and emotional point of view, we can also see that a space is thereby created - a 'clearing' in Martin Heidegger's phrase - where something new can take root and grow. A larger, symbolically richer dimension - the Arthurian mythos no less - which will resolve and transmute the chaos of sub-Roman Britain - is free now (should it choose) to invite Aquila into its story and allocate him a role.

If similar circumstances were to befall ourselves, would we be alive and awake to such a redemptive possibility? Could we perceive that with crisis comes opportunity and that it is precisely when night seems endless that dawn is close at hand. Or would we remain blind to this universal law, swept along like flotsam and jetsam by the rip tide of events?

In my previous essay I referred to St. Augustine's City of God as 'a profound act of sensemaking', an attempt to chart a path through the fog of confusion engendered by the fall of Rome. The Lantern Bearers, in many ways, is a fictional equivalent. It asks the same questions. Where do we turn when everything we know and cherish crumbles into dust? How do we respond? Do we fight, fly or freeze? Do we rage blindly against the enemy or do we subside into a sterile, apathetic blend of resentment and despair? What is the dominant motif of our lives? Sadness? Revenge? Mourning? Hate? What about hope? Can there be clear strategic thinking in the midst of burning homesteads and falling towers?

These are the questions Aquila wrestles with throughout the book. He is eighteen years old at the outset, a Commander of Horse in the Roman Auxiliaries, the last of the imperial forces active in Britain, the legions themselves having been withdrawn in 410 AD, forty years previously. When the order comes for this remaining garrison to leave as well, Aquila has to decide where his loyalties lie, with Britain or with Rome. He chooses the land of his birth, deserts his command, and returns home to the family farm. Two evenings later, the Saxons burst in. After a fierce fight, Aquila's father is killed and his sister carried into slavery, with Aquila himself stripped naked and tied to a tree. 'Leave him to the wolves,’ growls Wiermund the Saxon. 'He slew Wiergyls our Chieftain! They call the wolves our brothers, let the wolves avenge their kin!’ 2

A Jutish raiding party chances upon Aquila before the wolves can reach him. They take him with them to Juteland, where he lives for three years as a thrall, before the tribe sails back to Britain, not as opportunistic raiders now but as permanent settlers. Aquila escapes and finds himself at length in North Wales and the hill-top fortress of Ambrosius Aurelianus, Britain's rightful ruler, smuggled to safety as a child when Vortigern the usurper slew his father, King Constantine. Ambrosius, with Aquila's help, reclaims the land and drives the Saxons back. The novel ends with his coronation as High King and with Aquila finding a measure of peace and resolution after twenty years of inner and outer conflict.

Such a bald summary does not do justice for a moment to the book's intricate patterning and the deep mythic structures that open out into our consciousness as we read. The Lantern Bearers is a richly textured, multi-layered, and poly-dimensional work of art. For the sake of focus and conciseness I want to hone in on one particular episode, which though it occurs in Chapter Two (out of 22), serves as the thematic and symbolic heart of the story. The cover art from the Dutch translation (above) captures its spirit perfectly.

Night is near. The Roman galleys are almost ready to sail away, never to return. Aquila, 'as though in obedience to some last-minute order’ 3 leaves his ship and disappears back into the ancient fort of Rutupiae. He hides inside the Pharos, the mighty beacon tower, where every night for time immemorial the fire had blazed out as a testament and symbol that Rome-in-Britain was alive and thriving. But not this night. After some perfunctory searching, the Romans sail off without him. Alone now, in the silence of the great fort, Aquila climbs up and steps out onto the beacon platform:

The moon was riding high in a sky pearled and feathered with high wind-cloud, and a little wind sighed across the breast-high parapet with a faint aeolian hum through the iron-work of the beacon tripod. The brazier was made up ready for lighting, with fuel stacked beside it, as it had been stacked every night. Aquila crossed to the parapet and stood looking down. There were lights in the little ragged town that huddled against the fortress walls, but the great fort below him was empty and still in the moonlight as a ruin that had been hearth-cold for a hundred years. Presently, in the daylight, men would come and strip the place of whatever was useful to them, but probably after dark they would leave it forsaken and empty to its ghosts. Would they be the ghosts of the men who had sailed on this tide? Or of the men who had left their names on the leaning gravestones above the wash of the tide? A Cohort Centurion with a Syrian name, dying after thirty years' service, a boy trumpeter of the Second Legion, dying after two …

Aquila's gaze lengthened out across the marshes in the wake of the galleys, and far out to sea he thought that he could still make out a spark of light. The stern lantern of a transport; the last of Rome-in-Britain. And beside him the beacon stack rose dark and waiting … On a sudden wild impulse he flung open the bronze-sheathed chest in which the fire-lighting gear was kept, and pulled out flint and steel and tinderbox, and tearing his fingers on the steel in his frantic haste, as though he were fighting against time, he struck out fire and kindled the waiting tinder, and set about waking the beacon. Rutupiae Light should burn for this one more night. Maybe Felix or his old optio would know who had kindled it, but that was not what mattered. The pitch-soaked brushwood caught, and the flames ran crackling up, spreading into a great golden burst of fire; and the still, moonlit world below faded into a blue nothingness as the fierce glare flooded the beacon platform. The wind caught the crest of the blaze and bent it over in a wave; and Aquila's shadow streamed out from him across the parapet and into the night like a ragged cloak. He flung water from the tank in the corner on to the blackened bull’s-hide fire-shield, and crouched holding it before him by the brazier, feeding the blaze to its greatest strength. The heart of it was glowing now, a blasting, blinding core of heat and brightness under the flames; even from the shores of Gaul they would see the blaze, and say, 'Ah, there is Rutupiae's Light.' It was his farewell to so many things; to the whole world that he had been bred to. But it was something more: a defiance against the dark.

He vaguely, half-expected them to come up from the town to see who had lit the beacon, but no one came. Perhaps they thought it was the ghosts. Presently he stoked it up so that it would last for a while, and turned to the stairhead and went clattering down. The beacon would sink low, but he did not think it would go out much before dawn. 4

‘ … a blazing, blinding core of heat and brightness.’ That is how Sutcliff describes the centre of the blaze, and the blaze itself is the molten, dynamic core of the book. It is also a prophecy, a foreshadowing of a splendour to come, which Aquila - after he has suffered - will help make real and concrete. This seemingly pointless, arbitrary act sets a profound series of ripples in motion. It has a deep and lasting influence. Everything fans out and around from it.

Years later, after escaping from the Jutish camp, Aquila finds sanctuary in the woodland hermitage of the monk, Ninnias. One evening, while looking out over the forest ridges, the holy man tells him:

I used to come out here every evening, just at owl-hoot, to watch for Rutupiae Light … And then one night it was very late in coming; but it came at last, and my heart leapt up to see it as though it were a friend's face. And the next night, though I looked for it three times, it did not come at all. I thought, “The mist has come up and hidden it.” But there was no mist that night. And then I knew that the old order had passed, and we were no more part of Rome.

Aquila is astonished …

… his mind going back to that last night, after the galleys sailed, seeing again the beacon platform in the dead silver moonlight, the sudden red flare of the beacon under his hands. And two days march away this man had been watching for it, and seen it come. In an odd way, that had been their first meeting, his and the quiet brown man's beside him; as though something of each had reached out to make contact with the other, in the sudden flare of Rutupiae beacon. 5

What is the message for ourselves here? I think it is simply to never give up hope - to retain the awareness that everything has value, even misery and defeat, and that there are levels of meaning and connection that extend beyond our ability to perceive them in the here and now. As in Aquila's encounter with Ninnias, these links will become clear to us when the time is right. 'It is a holy ghost that works among the fallen,’ Anne Ridler as writes in her poem Taliessin Reborn, 'Nothing in the end is lost.’ 6

To have hope, we need a positive vision of the future - something to believe in, something to pull us forward and through. It is a pre-requisite. We are lost without this guiding star. In Man's Search For Meaning, Viktor Frankl's memoir of life in the Nazi death camps, the author reflects:

The prisoner who had lost faith in the future - his future - was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future, he also lost his spiritual hold: he let himself decline and become subject to moral and physical decay. 7

What goes for one goes for all. Without a vision the people perish, etc. The chief enemies of the 'red-pilled' - those who see how deep the rabbit hole goes - are what I call the 'three D's': Defeatism, Declinism, and Despair. Denethor (another 'D') in The Lord of the Rings, for instance, becomes immobilised by these inter-penetrating D's and ends up falling prey first to madness, then to suicide. There are other, related roads to ruin. As the writer John Solomon Bain put it in a response to my first essay, 'I think especially now there are two traps I see people fall into: (1) latching onto men, especially politicians, as saviours: (2) going full black-pill and embracing despair and nihilism. In the end, no matter how difficult, we must maintain faith in Christ.’

We need faith in Christ, faith in the future, and faith in ourselves. Not easy when darkness covers the land and the future had been blacked out in a bitter cloud of hopelessness. Such could indeed be our lot. How then do we punch out way out of the fog? By tapping into and invoking archetypal powers that resonate and chime with the ultimate dispeller of gloom - Christ the King and Judge, Christos Pantoktator, Christ as He will appear in glory on the Last Day, bringing down the curtain on all the apocalypses, macro and micro.

Circumstances, to an extent, might help draw this extra dimension out. Stressful times have the habit of digging down into and dragging up our latent nobility and grandeur. Alan Garner (a writer I will feature later in this project) refers to it in relation to his Alderley Edge childhood and the local legend of the Sleeping King:

During the Second World War when everything was very dark … I can remember my grandfather and my own parents discussing the legend and being more than half serious. They were saying, it's time for King Arthur to wake up now. Now is the time for him to come out and fight the last battle … In a dark hour what they turned to instinctively was their own legend, which had within it the seeds of salvation.

The white magician and Anglican mystic Dion Fortune (1890-1946) engaged practically and creatively with this mythic stream throughout the war. Together with her disciples she evoked the Arthurian archetypes and visualised archangelic forces guarding the country's shores. This was her war work - her defence of the realm - and who knows how vital it might have been? Britain, after all, remained unconquered, and Arthur, in a sense, did return. See this short essay by William Wildblood for an insightful appraisal. 8

Everything, ultimately, connects back to Arthur and the solar, kingly charism he embodies, like Solomon and David before him and Charlemagne and Alfred after him. He is the once and future king, and when the chips are down he will return. As far as Britain and the British go, he is embedded in the national psyche and encoded in the deepest recesses of our being. But the return of the King is a universal theme. Other countries and civilisations have their equivalents (e.g. Kay Kosrow, the legendary Shah of Persia, and many more. If we can laser in on this figure, therefore - imaginatively and intuitively - then we are giving ourselves a chance of pulling through and, more than that, of aligning our aim with the creative thrust of the emerging mythos - the next grand narrative - that will construct a new civilisation on the ruins of the old.

This is where Aquila finds himself at the end of The Lantern Bearers. Ambrosius has just been crowned High King at Winchester and a hard-earned, still partial but nonetheless emphatic victory has been won. After much personal and familial strife, Aquila has found peace with himself and his loved ones. There is order and stability in both the inner and the outer worlds. A space - a 'clearing' - has been created, and into it steps the figure of the Emperor. I say this because the man Sutcliff draws our attention to here goes on to be acclaimed Emperor of the West in her sequel Sword at Sunset (1963). I am reminded too of Valentin Tomberg's reflection on the Emperor in his Meditations on the Tarot (1967). The Emperor stands alone, he reminds us, with no court or retinue for company, just the wide canopy of sky and a single tuft of grass. 9

When order is forged from chaos, clutter discarded, and a clearing made, then extraordinary things can start to happen. Ambrosius has given the Romano-British a breathing-space, but this is a very pregnant pause, not an end but a beginning, not a completed work but a platform and a springboard for someone who will take his achievement onto a new, breathtakingly higher level:

'It is wonderful what one victory in the hands of the right man will do,’ Eugenus said musingly beside him. 'With a Britain bonded together at last, we may yet thrust the barbarians into the sea, and even hold them there - for a while.’

Aquila's hand was already on the pin of the door behind him, though he was still watching the thinning, lantern-touched crowd in the courtyard. 'For a while? - You sound not over-hopeful.’

'Oh, I am. In my own way I am the most hopeful man alive. I believe that we shall hold the barbarians off for a while, and maybe for a long while, though - not for ever … It was once told me that the great beacon light of Rutupiae was seen blazing on the night after the last of the Eagles had flown from Britain. I have always felt that that was' - he hesitated over the word - 'not an omen: a symbol.’

Aquila glanced at him, but said nothing. Odd, to have started a legend.

'I sometimes think that we stand at sunset,' Eugenus said after a pause. 'It may be that the night will close over us in the end, but I believe that morning will come again. Morning always grows again out of the darkness, though maybe not for the people who saw the sun go down. We are the Lantern Bearers, my friend; for us to keep something burning, to carry what light we can forward into the darkness and the wind.’

Aquila was silent a moment; and then he said an odd thing. 'I wonder if they will remember us at all, those people on the other side of the darkness.

Eugenus was looking back towards the main colonnade, where a knot of young warriors, Flavian among them, had parted a little, and the light of a nearby lantern fell full on the mouse-fair head of the tall man who stood in their midst, flushed and laughing, with a great hound against his knee.

'You and I and all our kind they will forget utterly, though they live and die in our debt,’ he said. 'Ambrosius they will remember a little, but he is the kind that men make songs about to sing for a thousand years.’ 10

The 'tall man' with the 'mouse-fair head' is Arthur (Artos, Sutcliff calls him), still a young warrior, still a lieutenant of Ambrosius, but not for much longer. The time for him to step forward and assume his high destiny is fast approaching. Sword at Sunset tells his story, from three days after this coronation scene to his passing from this world in the Island of Apples forty years later.

For now, I would like to conclude with a practical suggestion. Waking the beacon and clearing a space, as I see it, are two ways of saying the same thing - two facets of the same phenomenon. One way or another, a clearing is made, and there is space and light where before there was neither, and the Royal One has room to appear.

We can wake that beacon. We can make that space. Not only can but must. Why not try this exercise once or twice a day for seven days after reading this essay? Maybe we can practice it together and see what seeds are planted and what it brings up over time. I have adapted it from one of Dion Fortune's meditations. Imagine a triangle pointing upwards in the form of three circles. Arthur sits in the right-hand circle with crown and sceptre and orb, the red dragon of Logres fluttering in the torchlight beside him on a banner of gold. On the left is Galahad, holding the Grail out before him, pushing it forward almost, as if inviting us to drink. He is standing at a quayside in front of a ship with a white sail and the towers, domes and spires of a small town. The sun rises behind him, while gulls wheel around in the sky above. The topmost circle shows the Virgin and Child, standing on the slopes of Glastonbury Tor, with the tower of what was once St. Michael's church in the background and the mid-day sun pouring down its rays of power and grace upon them and, by extension, upon ourselves. The Infant Saviour's left hand holds an open book while his right is raised in blessing, placing Galahad and Arthur under his aegis and bringing his benediction to our own lives as we perform the visualisation and return back afterwards to the world.

This is my suggestion for waking the beacon - my 'two penn'orth' if you like. It is an imaginative exercise because that is the way my mind works. What other ways might there be? What else might we do? In art, in politics, in culture, in our personal relationships, on our own, or in society as a whole. Aquila, on the beacon top, pulls out 'flint and steel and tinderbox', strikes out fire and kindles the waiting tinder and sets about waking the beacon. What are our equivalents? Where is our flint, our steel, our tinderbox? Where do we find them? What do we do when we find them? How do we find space for truth and fashion a clearing for the Sun of Justice to appear? That is the task and vocation and necessity of our time.

Rosemary Sutcliff, The Light Beyond the Forest (The Bodley Head, 1979), p.10.

Rosemary Sutcliff, The Lantern Bearers (Oxford University Press, 1959), p.39.

Ibid, p.21.

Ibid, pp.24-26.

Ibid, p.122.

Anne Ridler, The Nine Bright Shiners (Faber and Faber, 1943)

Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning (Rider, 2004), p.82.

See also, Gareth Knight, The Magical Battle of Britain (Skylight Press, 2012)

Anonymous, Meditations on the Tarot (Element Books, 1985), p.78.

Sutcliff, The Lantern Bearers, pp. 304-305.

Hi John - you likely won't see this until Monday morning, but for what it's worth - I am thinking of doing your meditation (or some variation of it) during tonight's lunar eclipse...

I'm sorry I haven't commented sooner...quite honestly I've been having great difficulty attempting to compose words which sufficiently express my thoughts in regard to what you are (I believe) attempting to achieve here at "Secret Fire".

I did enjoy the first essay and this second one even more-so!

Carol