The Last Battle is not The Return of the King and Aragorn is a different figure to Tirian, the last King of Narnia. Aragorn at once restores an ancient royal line and inaugurates a new dynasty. Tirian’s reign is brought to an abrupt close by nothing less than the end of the world. The main action of The Lord of the Rings takes about a year to unfold while The Last Battle is done and dusted in three days. Tolkien’s epic unfolds over vast geographical spaces while Lewis’s eschatological drama hones in one physical point - a hill-top stable in Lantern Waste in the western wilds of Narnia.

These differences between the texts make the similarities more apparent. Both kings stand for tradition and truth at a time when the enemy’s lies have hardened hearts, darkened minds, and spread confusion and uncertainty. There are moments when they feel lost and beaten down, yet their faith in transcendent pushes them over the line and leads them to fulfilment. They become who they were born to be. They attain authentic Being, and they do this in realms that are teetering on the brink of ruin. They pick up arms against chaos and reinstate the vertical dimension.

Tirian, to start with, is much younger and vastly less experienced. Aragorn is already eighty-seven when The Lord of the Rings begins, though of course he looks and acts much younger. He has commanded armies, travelled widely, and endured decades of thankless service as a Ranger of the North. Tirian is raw and uncut - inherently noble, yet young and untested. He is ‘between twenty and twenty-five years old,’ Lewis tells us. ‘His shoulders were already broad and strong and his limbs full of hard muscle, but his beard was still scanty. He had blue eyes and a fearless, honest face.’

I think this helps explain Tirian’s initial naivety and political unconsciousness. Rumours sweep Narnia that Aslan has returned. Everyone says so - birds, squirrels, stags, even a merchant from Calormen. The King accepts it all uncritically, like an individual today who automatically believes everything he or she is told by the mainstream media. He is spellbound and paralysed. ‘I cannot set myself to any work or sport today,’ he tells his lieutenant, Jewel the Unicorn. ‘I can think of nothing but this wonderful news.’

Then Roonwit the Centaur arrives and presents them with a shockingly different scenario. Roonwit is an astrologer, and he tells the King that the stars do not foretell the return of Aslan but rather the approach of upheaval and disaster. The rumour that Aslan is back, says Roonwith, is a lie.

Tirian reacts with unconscious violence:

‘A lie!’ said the King fiercely. ‘What creature in Narnia or all the world would dare to lie on such a matter?’ And, without knowing it, he laid his hand on his sword hilt.

‘That I know not, Lord King,’ said the Centaur. ‘But I know there are liars on earth; there are none among the stars.’1

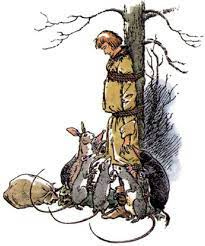

Events then take a precipitous turn as the King is swept up by the evil which has been lurking in Lantern Waste and is now ready to stride into the open. Questions need to be asked here about Tirian’s stewardship of the land. How did he not know that the crafty ape Shift had been keeping a false Aslan in the stable and displaying him to susceptible Narnians? Why was he unaware that Shift had persuaded the Calormenes to steal into the country and take commercial and military advantage? It is what we would call today a colossal intelligence failure. Tirian has fallen asleep at the wheel, but now in a series of hammer-blows he is decisively stripped of all complacency and delusion. The bedrock of reality is exposed to him. The evil which has grown unchecked on his watch is made manifest, and a day which opened with such optimism ends with Tirian tied to an ash tree, with a bleeding lip and all alone apart from the kindly animals who bring him a small but welcome supper.

Left alone again once the animals have gone and divested of all power and authority, the hopelessness of Tirian’s situation becomes plain. ‘He thought of other Kings who had lived and died in Narnia in old times and it seemed to him that none had been so unlucky as himself.’ Then he remembers the children from another world who had appeared in ages past and brought aid to his ancestors Rilian and Caspian. ‘But it was all long ago,’ he decides. ‘That sort of thing doesn’t happen now.’ He goes further back still though and an even more archaic story wells up in his mind, that of the four children who had fought with Aslan and defeated the White Witch and become ‘great Kings and lovely Queens,’ whose reign ‘had been the golden age of Narnia.’

Tirian knows what to do instinctively now. He is on the right path and tuned in to forces that can help him. This is the book’s first turning point. In his grief and desperation, crying out from the core of his being, he calls on that world’s equivalent of God and the Saints. It is Tirian’s De Profundis:

‘Aslan and children from another world,’ thought Tirian. ‘They have always come in when things were at their worst. Oh, if only they could now.’

And he called out ‘Aslan! Aslan! Aslan! Come and help us Now.’

But the darkness and the cold and the quietness went on just the same.

‘Let me be killed,’ cried the King. ‘I ask nothing for myself. But come and save all Narnia.’

And still there was no change in the night or the wood, but there began to be a kind of change inside Tirian. Without knowing why he began to feel a faint hope. And he felt somehow stronger. ‘Oh Aslan, Aslan,’ he whispered. ‘If you will not come yourself, at least send me the helpers from beyond the world.’ Then, hardly knowing that he was doing it, he suddenly cried out in a great voice:

‘Children! Children! Friends of Narnia! Quick. Come to me. Across the worlds I call you; I Tirian King of Narnia, Lord of Cair Paravel, and Emperor of the Lone Islands!’

And immediately he was plunged into a dream (if it was a dream) more vivid than any he had had in his life.

The sincerity of Tirian’s cry, the purity of his heart, and the authenticity of his need, breaks the barriers of time and space and finds its echo in England where the Seven Friends of Narnia, sensing that something is wrong, have come together in counsel. Tirian appears to them as they are finishing their meal. Peter, the High King, charges him to speak but he is unable to do so and vanishes from their sight. He wakes abruptly, still tied to the tree, but straightaway Jill and Eustace, the two youngest members of that party, are there with him. Quickly they untie his bonds. It has taken them a week in English time to arrive, but from Tirian’s perspective they came straight after his prayer and vision. Once he had drilled down to the heart of things and touched the core of reality, then Aslan’s response was immediate and effective.

From this point on, Tirian is able to take back a measure of control and plot a conventional storybook fightback. Things are looking up and it is hard to believe that the whole Narnian universe only has two days left to run. He takes the children to a watch tower, built in his grand-father’s day in the uplands of Lantern Waste. Like Caspian before him and Alfred the Great in English history, he now has a hidden base from which to develop strategy and tactics.

It is not yet time for an open declaration of war. Tirian is wise and level-headed enough to recognise this. Is there a lesson here for ourselves? Are we honour-bound to always display our intentions publicly or are there times when a more cloak and dagger, even deceptive, approach is called for? Tirian, for instance, does not hesitate to disguise himself and the children as Calormene soldiers. Is it possible or desirable where we are now to ‘look like’ the enemy yet all the time be working secretly for his downfall. Discernment, as always, is required.

The loyalists make steady progress. Jewel is rescued from captivity, while Roonwit is bringing reinforcements from Cair Paravel. The next shock comes when they encounter a group of Dwarfs who Tirian confidently expects to win over now that he is able to expose the lies of Shift. But the Dwarfs refuse to follow. Having been taken in once, they Won't Get Fooled Again. They have become cynical and hard-bitten. ‘I don’t think we want any more kings,’ growls Griffle, the Chief Dwarf …

‘… no more than we want any Aslan. We’re going to look after ourselves from now on and touch our cap to nobody - See? ‘That’s right,’ said the other Dwarfs. ‘We’re on our own now. No more Aslan, no more Kings, no more silly stories about other worlds. The Dwarfs are for the Dwarfs.’

To transpose this attitude to the contemporary scene, we could say that they stand at the other extreme to the gullible, MSM-believing ‘normie.’ These ‘black-pilled’ Dwarfs inhabit a ‘post-truth world’ where all narratives are baseless and exploitative. Conspiracies and hidden string-pullers lurk everywhere. There is no overarching pattern, no good or evil, just power games played by equally self-serving power blocs. There is no grace, no magic, no salvation - just mutual suspicion in a post-modern hall of mirrors.

More and greater shocks await our band of legitimists, bolstered now by Poggin, the only Dwarf to rally to the King. They behold the Calormene god Tash, with its beak and claws and twenty curved fingers, gliding northwards through the woods, ‘as if it wanted to snatch all Narnia in its grip.’ The scale of the evil they are contending with is now alarmingly clear:

‘It seems then,’ said the Unicorn, ‘that there is a real Tash after all.’

‘Yes,’ said the Dwarf. ‘And this fool of an Ape, who didn’t believe in Tash, will get more than he bargained for. He called for Tash: Tash has come.’

‘Where has it - he - the Thing gone to?’ said Jill.

‘North into the heart of Narnia,’ said Tirian. It has come to dwell among us. They have called it and it has come.’

Tirian sees that the time for subterfuge has gone. The disguises come off as they march East to join Roonwit and his reinforcements. But the meeting never happens as the plot turns again. At the mid-point of the book, Farsight the Eagle brings the most devastating news imaginable. The ultimate nadir, lower even than Tirian’s binding to the tree, is reached:

‘Two sights have I seen,’ said Farsight. ‘One was Cair Paravel filled with dead Narnians and living Calormenes: The Tisroc’s banner advanced upon your royal battlements: and your subjects flying from the city - this way and that, into the woods. Cair Paravel was taken from the sea. Twenty great ships of Calormen put in there in the dark of the night before last night.’

No-one could speak.

‘And the other sight, five leagues nearer than Cair Paravel, was Roonwit the Centaur lying dead with a Calormene arrow in his side. I was with him in his last hour and he gave me this message to your Majesty: to remember that all worlds draw to an end and that noble death is a treasure which no-one is too poor to buy.’

‘So,’ said the King, after a long silence. ‘Narnia is no more.’

Where do you go from here? ‘For a long time they could not speak nor even shed a tear.’ Then Jewel makes it simple and direct:

‘Sire,’ he said, ‘there is now no need of counsel. We see that the Ape’s plans were laid deeper than we dreamed of. Doubtless he has long been in secret traffic with the Tisroc and sent him word to make ready his navy for the taking of Cair Paravel and all Narnia. Nothing now remains for us seven but to back to Stable Hill, proclaim the truth, and take the adventure that Aslan sends us. And if, by a great marvel, we defeat those thirty Calormenes who are with the Ape, then to turn again and die in battle with the far greater host of them that will soon march from Cair Paravel.

And so they fight on, aligned to the Truth and accepting of their fate. They watch discreetly from behind the stable as Narnians are lied to and manipulated - ‘gaslighted’ in today’s parlance - and Aslan is blasphemously conflated with Tash. Disturbing events take place and it is hard to know what to do:

Tirian stood with his hand on his sword-hilt and his head bowed. He was dazed with the horrors of that night. Sometimes he thought it would be best to draw his sword at once and rush upon the Calormenes: then next moment he thought it would be better to wait and see what new turn affairs might take.

But when the Kairos - the supreme moment - comes, Tirian knows exactly what to do. Because he is so attuned now to the Real, there is no gap at all between thought and deed. The noble Boar is resisting being dragged into the stable to meet ‘Tashlan’ and …

… when Tirian saw that brave Beast getting ready to fight for its life - and Calormen soldiers beginning to close in on it with their drawn scimitars - and no-one going to its help - something seemed to burst inside him. He no longer cared if this was the best moment to interfere or not.

‘Swords out,’ he whispered to the others. ‘Arrow on string. Follow.’

Next moment the astonished Narnians saw seven figures leap forth in front of the Stable, four of them in shining mail. The King’s sword flashed in the firelight as he waved it above his head and cried in a great voice:

‘Here stand I, Tirian of Narnia, in Aslan’s name, to prove with my body that Tash is a foul fiend, the Ape a manifold traitor, and those Calormenes worthy of death. To my side, all true Narnians. Would you wait till your new masters have killed you all one by one?’

It is a seminal moment - the books’ third and thus far greatest turning point. The archetypal has become actual. Arthur has returned to his people. Aragorn unfurls his standard. The Great Monarch is among us.

We have now reached the end of Chapter Eleven. The Last Battle has sixteen chapters in all. This great unveiling - this grand declaration on Tirian’s part - brings us to the end of the story in many ways. There are no more plot twists on the earthly plane. What follows is a chapter and a half of fighting, before the rest of the tale unfolds in eternity, on the other side of the stable door. This is the book’s fourth and final turning point, the apotheosis of all that that has gone before. Tirian and his comrades have achieved their mission. They have proved themselves, one might say, as Heroes of the Fourth Turning. Time and history are rolled up like a scroll now and the old dispensation diminishes and fades in the light of the wonder and glory that now sets the tone:

It is hard to explain how this sunlit land was different from the old Narnia as it would be to tell you how the fruits of that country taste … The difference between the old Narnia and the new Narnia was like that. The new one was a deeper country: every rock and flower and blade of grass looked as if it meant more. I can’t describe it any better than that: if you ever get there you will know what I mean.

As for Tirian, he has fulfilled his vocation as the Sovereign whose destiny it was to lead his people from time into eternity. ‘Well done,’ says Aslan. ‘Well done, last of the Kings of Narnia, who stood firm at the darkest hour.’

Tirian succeeds through a deep and sustained act of Platonic anamnesis - the remembrance and invocation of what is real and true and the grace to let his actions flow forth from that source. His naivety and complacency is burned away, leaving a space - a ‘clearing’ - for the gold that is his essential nature to shine out ‘like shook foil’ and win the day. Falsity cannot stand against this level of truth, this living flame, this embodiment of quality and goodness. Tirian is aligned with the Sun and becomes thereby invincible. Setbacks recede into insignificance and destiny propels him on.

This is what we are all called to do and be at this time of transition. We are all kings and queens in this sense - prophets and priests too. The world needs our witness and example. If Tirian, for example, had not risen to the challenge as he did, then the Narnian apocalypse might have been so much more bloody and chaotic than it was. Who knows what impact we might have? We have a responsibility to be present and awake as Tirian was, so that when the bell sounds and the Kairos rushes on us we might blaze forth ourselves in the splendour of the truth - Veritatis Splendor - as Tirian did and as do all the saints and prophets and warrior kings of all the ages.

May Aslan say ‘Well done’ to us as well one day as we take our place in the great procession, voyaging ‘further up and further in’ with all those heroes in that Blessed Land on the other side of the stable door.

The quotations in this essay are all from The Last Battle (Puffin Books, 1978). As I have quoted so extensively from this single source I have not used page references as I felt they might needlessly clutter the page. It’s a short book anyway and everything is easy to find.

The illustrations are the colourised versions of Pauline Baynes’s originals.

The painting at the top is The Last Angel (1942) by Nicholas Roerich.