Why does Aquila light the beacon? The culture of reductionism, which has poisoned the well-springs of the West so deeply, would assert that the root causes are subjective and that they surge up from below. For three days he had known that he would be leaving his country forever and had been wrestling with the question of who he really was - a Roman or a Briton. For so long it had been possible - desirable even - to be both, but now the familiar Romano-British milieu that Aquila had been born into had only a few hours left to run. Rome-in-Britain was soon to be no more. It was time to choose, and the stress of the choice and the psychological impact of deserting Rome demanded an outlet and found expression in the apparently arbitrary act of waking the beacon.

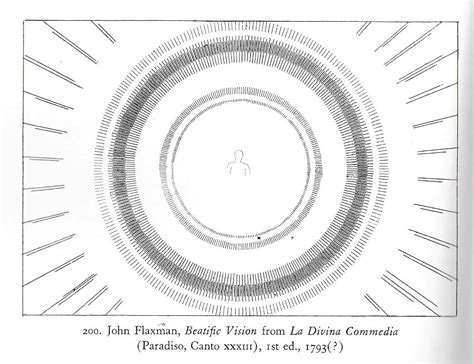

The Europe of the Middle Ages might have seen things differently, however. It believed in a hierarchy - spiritual, imaginative and dynamic - with movement between the various spheres instigated from above, not below: 'a whirling carnival of dominion and service' in C.S. Lewis's phrase. Dante’s Commedia bears eloquent and unparalleled witness to this worldview. As the poet shows us in his final canto, it is the highest level of all, that of the Blessed Trinity, that guides and directs the cosmos - 'the love,’ as he says, ‘that moves the sun and the other stars.’ It draws us on and up, pulling us out of Hell and propelling us through a series of ever greater and more meaningful wholes until our appetites are purged, our vision is cleansed, and we are able to connect with what is fully real.

This is the regenerative, Pentecostal power that inspires Aquila and reveals itself through his deed. It is the heights that set the agenda, not the depths. Aquila, at the time, is unable to discern th purpose behind what he does, but he perceives it later, and so do we. In Sword at Sunset (1963) - Sutcliff's sequel to The Lantern Bearers - there is one episode in particular which mirrors Aquila's gesture and at the same time carries it forward and takes it onto the next level. Sword at Sunset is a rare Sutcliff novel that is aimed at adults rather than children. So there is no shortage of drama and intensity. There are many vivid moments, but this one - the acclamation of Artos as Emperor - stands out because in it a higher archetype breaks through into the time-bound, material world and starts dictating the tempo of events. There is someone or something driving what occurs here. A power greater even than that of the already semi-legendary British war leader is at work. Yeats is on the same page in The Statues when he meditates on the Easter Rising of 1916 and the relationship between the mythical and the historical:

When Pearse summoned Cuchulain to his side. What stalked through the post Office? What intellect, What calculation, number, measurement, replied?

Artos is the nephew of the recently-deceased High King, Ambrosius Aurelianus. He has long been the King’s most successful and respected captain, but is confronted now with a barbarian attack of terrifying dimensions - a scale of manpower and co-ordination which the fledgling post-Roman British state has never faced before. Yet he scatters the foe at Badon Hill in such an emphatic style that for the foreseeable future the Saxons can no longer threaten the integrity of the country. Artos is acclaimed Emperor by his troops immediately after the battle. The impromptu ceremony begins (and continues) in a spontaneous and unplanned fashion:

They were all round me … a sea of torch-lit faces turned up to mine as I sat the great battle-weary horse above them. Men were thrusting in for a closer look, to touch my knee or my sword sheath or my foot in the stirrup, and all I wanted was to get them into some kind of order and back as far as the wagon laager for the night. And then - even now I do not know how it started - one of the veterans, with enough years behind him to remember the old way of things and the last Imperial troops still in Britain, set up a shout of “Hail Ceasar!” And those nearest about him caught it up, and the thing spread like ripples in a pool, until the whole of the war-host - or such of them as were mustered there - were shouting, bellowing it out and beating it home upon their shields and the shoulders of their comrades.

They lift him up, bear him aloft, and set him down on an ancient boulder:

… a block of lime stone, green on the north side with moss almost as the grass about it, but as the torches beat upon it, the probing glare picked out strange circles within circles of eternity, that the weather had all but worn away …

And on this great rough-hewn boulder, where I think the forgotten kings of a forgotten people had been enthroned, they set me down for my own throning - not as High King, after all, but as Emperor, even as his troops had crowned Magnus Maximus my Great Grand-sire Emperor …

And I was made Emperor, I think, with something of the rites of every Faith that could still claim a follower among the war-host. Pharic and his Caledonians set a circle of seven swords point down in the grass about me, and in all that followed, no man entered the circle between the two swords at my face, and I was chrismed with armour-grease brought from the captured wagons, but the priest who anointed me was a wild-eyed creature who came out of the dark with the villagers, a Christian priest by his frock of undyed sheep’s wool and his shaven forehead, but he wore the Sun cross carved from red amber around his neck, and he made the King marks on my forehead and breast, feet and hands, not in the Christian form but in older symbols. And my own men brought a hastily made circlet of oak leaves from the hill-spinner close by, where the young leaves still retained a flush of their spring-time gold, and thrust it down on my head for an Imperial diadem; and someone, who, I never saw, hoisted an old cloak on a spear point above the heads of the crowd and tossed it to those nearest me, who caught and flung it about my shoulders. It was ragged, and spattered at the hem with dried blood, but it was of wine-red so deep and rich that in the torch-light it had the proud glow of the Purple. I got up and stood before my war-host while they roared their acclamation, aware of the Purple and the Diadem as though I were clothed in flame. My sword - I did not remember having drawn it - was naked in my hand. I felt the great carved stone at the back of my heel, and something in me, in the touch of my heel against the stone, in my very loins that linked me with the earth and the gods and the stones of the Earth, and the Sun and the Power of the Sun, and in the thing in the dark at the back of my head that came from my mother’s world, and knew the secret of the strange concentric circle that my father’s world had forgotten, told me that this was not a throne but a coronation stone like the Lia Fail of the High Kings of Erin, a stone for the King to stand on at his king-making, and I sprang on to it and flashed up my sword to the shouting war-host, and all around me a thousand weapons were tossed up in reply, and for a while and a while I knew my feet one with other feet that had been planted on that flaking stone, and other men’s hearts beating in my breast, and a wild weeping exultancy swept through me and on through the human sea around me …

So I stood among them, alone in my circle of seven swords, and looked down on the roaring sea of torch-lit faces, chilled suddenly by a foreshadow of the loneliness above the snow line. And when at last the tumult sank enough for me to make myself heard, I cried out to them in the greatest voice that I could muster, that it might reach to the furthest fringe of them. “Soldiers! Warriors! Ye have called me by the name of Caesar, ye have called me to be your Emperor as your great grandsires called mine, whose seal I carry in the pommel of my sword. So be it then, my brothers in arms. After forty years there is an Emperor of the West again … it is in my heart that few beyond our shores will ever hear of this night’s crowning, assuredly the Emperor of the East in his golden city of Constantine, will never know that he has a fellow; but what matters that? The island of Britain is all that still stands of Rome-in-the-West and therefore it is enough that we in Britain know that the light still burns. We have fought today such a battle as the harpers shall sing of for a thousand years! Such a battle as the women shall tell of to the bairns at bedtime to make them bold, and the sound men whose father’s fathers our great grandsons shall beget, shall speak of when they boast among themselves at the harvest feast. We have scattered the Sea Wolves so that it will be long and long before they can gather the pack again. Together, we have saved Britain for this time, and together we shall hold Britain, that the things worth saving shall not go down into the dark!” 1

This scene is to Sword at Sunset what Aquila’s waking of the beacon is to The Lantern Bearers. It is the symbolic heart and centre of the book - a light shining in a high place; a bold and instantaneous revelation of the truth. Like Aquila’s blaze, it brings both comfort and hope, and there is a wealth of meaning to be gleaned in both the description of the event and the contents of Artos’s speech. Without seizing foreign land, without setting foot outside the island, just by standing firm and holding up an ideal, Artos becomes the Emperor. He does not grasp at the purple. He does not need to. The purple is bestowed upon him, by dint of what and who he is. There is nothing external here. This is an inner quality - a quality of Being - which finds its inevitable echo and response in the recognition of Artos not just as High King - as Ambrosius had hoped he would become - but as Caesar.2

Creative writers, at their best, are essentially shamanic figures. The impulse, again, emanates from the higher, immaterial realms. A story seeks a writer out, shakes him or her like a dog, and makes itself manifest through the words that emerge from the struggle. Terry Eagleton puts it neatly in a recent essay on T.S. Eliot:

The individual, not least the individual author, is of relatively trifling significance. He or she is merely the tip of an iceberg whose depths are unsearchable.

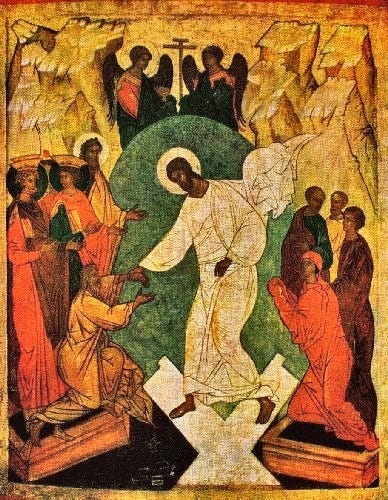

I cannot find the article now but I remember reading on this wide-ranging Sutcliff site that the figure of Artos completely possessed her during the writing of the book. She would start at 6 am, finish at 2 the next morning and begin again four hours later. I should add that when I say ‘possessed’ I do not mean this in the usual negative sense. The author remarked in the same piece that the writing of Sword at Sunset was an intensely fulfilling time for her. My point is that when writers get into this kind of ‘zone’ then the truly deep levels start to open up, where myth and history co-incide and past and future meet. We are rooted creatures, anchored, as Eagleton says, in the unsearchable depths of the past, but it is the future that reaches out to us, as in the Harrowing of Hell, across the abyss of time, hauling us out of stasis and calling us forward 'Behold! I make all things new.’ 3

Such things happen - take, for instance, the visions of cataclysm and slaughter C.G. Jung experienced in the months prior to August 1914. Shortly afterwards he underwent a soul-shattering descent into the archetypal unconscious, which gave birth at length the remarkable Red Book.4 Seen in this light, Sutcliff's account of Artos’s coronation could just as much be a prediction of an event yet to come as an evocation of a historical scene. Some would posit, perhaps, that Arthur did indeed return during the Second World War in the form of Sir Winston Churchill. I would respond that yes, he did, but only in a partial fashion, just enough to get the country through and keep the enemy at bay. What Sutcliff describes is on a different scale - a prefiguration of a much more decisive and long-term Arthurian intervention.

Remember too that Britain, apart from the Channel Islands, remained unconquered throughout the war. Enemy forces at no point set foot on mainland soil. They wreaked tremendous havoc from the air, of course, but the territorial integrity of the UK remained intact. The same cannot be said for the Britain Ambrosius and Artos fight to restore. Four hundred years of Roman civilisation had given way to chaos and collapse as Angles, Saxons, Picts, Jutes and Scots took advantage of the power vacuum, violating the land with growing determination and ever-increasing numbers. Again, the reductionist mindset might claim that Sutcliff's protagonists are driven by trauma and shock to fight tooth and nail to preserve and claw back the known, comfortable world of yesterday. Turn the perspective upside down, however, and what we see instead is the high archetype of the Return of the King making his through the actions of these characters. The key point is that this is what it takes - this level of trauma and disturbance; this loss of order and coherence - for illusion to dissolve and Reality (with a capital R) to come roaring back, in the outside world at first and then, crucially, in our hearts and minds. A space - a 'clearing' - is created, where the King can come into his own again, just as Aragorn does when he enters Minas Tirith after a night of horror and woe to bring healing, hope and inspiration at an hour when all had appeared lost.

One hopes, of course, that it does not come to this. The themes of restoration and renewal are woven deeply into the fabric of the universe, so a re-orientation towards the holy and Divine will happen in time anyway. It is as inevitable as day following night. It would appear, however, that some kind of down-going is on the cards. We have lived through a few bad things of late - I don't need to say what they are - and yet the West careers blindly on, mired in illusion and eaten up with a weird blend of hybris and self-hate. What will it take to wake us up?

Maybe this is how the pattern has to unfold? The King needs to suffer, die, and fall asleep before he rises again in glory. There are no short cuts. We have to pay our dues. Suffering and death are woven into the fabric of the universe as much as restoration and renewal. The only difference is that it is the latter pair that have the last word. We see this most clearly in the Easter story. It is also the theme of David Jones's two great Arthurian poems, The Hunt and The Sleeping Lord, which we will study in the next essay here. Aragorn himself endures a long and obscures apprenticeship, and before he can get anywhere near Minas Tirith he has to descend into the underworld - à la Jung - and tread the Paths of the Dead, a terrifying sojourn which strikes fear into the stoutest of hearts. Only then, after this trial and purification, is he able to unfurl his banner at the Stone of Erech, a rock on a hillside not unlike the boulder upon which Artos is crowned: ‘… round as a great globe, the height of a man, though its half was buried in the ground. Unearthly it looked, as though it had fallen from the sky, as some believed, but those who remembered still the lore of Westernesse told that it had been brought out of the ruin of Númenor and there set by Isildur at his landing.’ 5

If we are to get through whatever level of darkness awaits, then we will need a positive, constructive vision of the future. We need to believe that there is a future for ourselves, first of all, then for the West, then for the world as a whole. Aragorn is imbued with exactly this vision. He knows where he is going and is conscious of the high destiny waiting to be claimed on the other side of the tunnel. It motivates and energises him and brings focus and resolution to the men that follow him.

How are we to build and maintain this type of vision right where we are now at this low point of the civilisational arc? In an era of dissolution, how do we convince ourselves and others that rebirth and regeneration are truly on the way; that they will inevitably succeed this time of degeneration and decay? It might be helpful, as a starting point, to meditate daily upon the image of the phoenix - to really try to embed it in our minds - this symbol which carried so much significance for that force of creative nature, D.H. Lawrence:

Another potent step, I feel, would be to memorise Artos’s coronation speech - to deeply interiorise it and write it, as it were, in letters of gold on our hearts. If you are not in Britain, you can replace that word with wherever you are or wherever you belong to or whatever you hold most dear. It is a bold and defiant statement in the mould of Churchill’s war-time speeches. It raises morale, stiffens the sinews, raises the stakes, and gives us a razor-sharp sense of who we are and what we are fighting for.

We are not alone. That is the key message in this for me, and this applies to both time and space. The great ones who came before are with us - the ancestors; the Communion of Saints. Those yet to come are urging us on, and the Heavenly spheres reach down and inspire us, warming our hearts and firing our minds. We are part of a great chain of beacons, as in Nicholas Roerich’s painting, Fires of Victory:

From Aquila to Artos to ourselves ... on and on the fires are lit, from one lantern bearer to another. The story never ends. There is always a next chapter; always a sequel. The risk, the honour, and the opportunity to carry on the tale are ours.

C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (Oxford University Press, 1942), p.137.

Rosemary Sutcliff, Sword at Sunset (The Book Club, 1963), pp. 364-367.

Apocalypse, 21:5

For a detailed, impassioned and prophetic meditation on The Red Book, I would recommend Peter Kingsley’s monumental Catafalque (Catafalque Press, 2018). Also worth a look is any video on the Uberboyo YouTube channel relating to this book. I’ve picked up a lot from this guy. I like his energy and dynamism. Take this short, recent one here, for example.

J.R.R. Toklien, The Lord of the Rings (George Allen and Unwin, 1966), p. 820.

"If we are to get through whatever level of darkness awaits, then we will need a positive, constructive vision of the future. We need to believe that there is a future for ourselves, first of all, then for the West, then for the world as a whole."

This is a good encapsulation.

Having ideals is important. And the more those ideals align with what is good and true, the better they will be both in themselves and in pragmatic terms as well.

Unfortunately, many people misunderstand the nature of ideals. They think that ideals are just a delusional hope that we can avoid hardship or a merely aesthetic aversion to difficulty or something like that. I'm sure you've read many who express sentiments of that nature.

One example that casts doubt upon this is the Christian hermits. Few lived more austerely than them, and yet who had higher ideals?

I believe it just comes down to the fact that life has both spiritual and material aspects and we have to act in accordance with both, though it's not easy. And one aspect of that is aligning ourselves with the good, through our ideals and acting in accordance with them.