One of the most striking features of the past three decades has been the way in which liberalism has conducted a complete volte face from how it presented itself in the early 1990s. It had the air in those days, at least in the West, of a benign ring-master, a system of benevolent neutrality giving equal space to a wide variety of ideologies and lifestyles. That feels a long time ago now. Liberalism today appears more concerned with enforcing correct behaviour and even thought than providing a free, respectful space for different cultures and worldviews to thrive in. Some commentators, such as Bari Weiss and David French, seem to think that the great clock of liberalism can be dialled back and that the relative equanimity of thirty years ago will then be restored. It is a matter for them of curbing excesses and bringing the grown-ups back into the room. Others - post-liberals in the mould of Sohrab Ahmari, Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule - take the view that liberalism’s increasing militancy is a feature not a bug, and that authoritarian extremism was baked into the liberal project right from the start. Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed (1872) is a good point of reference here, especially the way the older generation of liberals, represented by Stepan Verkhovensky, unwittingly clear the ground for the breed of nihilistic revolutionaries, embodied by Stepan’s Satanic son, Pyotr, who will persecute and denounce everyone belonging to the past, including their former mentors. We see a foreshadowing here of how woke activists, in our own time, have turned with such venom against former liberal icons such as J.K. Rowling.

These concerns about liberalism’s ultimate trajectory were shared and brilliantly articulated for over fifty years by the recently deceased Pope Benedict XVI (Joseph Ratzinger). As Larry Chapp remarks:

He embraced many elements of what we conveniently label ‘liberal democracy’, but he understood well that its greatest virtues are rooted in the increasingly vague memory of the Christian intellectual legacy, the purely formal juridical categories of liberal democracy issue forth into a false notion of freedom and a false anthropology. Thus is modernity at a great crossroads. We now stand at the precipice of a dystopian technocratic destruction of the last remnants of the Christian doctrine of human specialness.

Therefore we face a choice for or against Christ, and therefore for or against the full horizon of the human spiritual landscape. Pope Benedict’s great friend and collaborator, Hans Urs von Balthasar, called this choice our ‘Ernstfall’ moment, which is just a fancy way of saying that sooner or later modernity is going to force upon all of us a crisis moment of choosing, wherein, ironically, not to choose will be to choose.

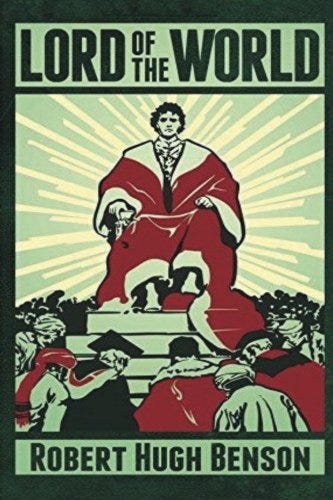

This is exactly what happens in R.H. Benson’s dystopian novel Lord of the World (19071 People choose between Christ and an augmented version of modernity, and the overwhelming majority - certainly in England, where the story is principally set - opt for the latter. The early-twenty-first-century world Benson creates is so overwhelmingly secular - so crushingly this-worldly - that the very idea of God becomes unreal and fantastical, a jarring impossibility:

‘Until our Lord comes back,’ he (Father Percy Franklin) thought to himself; and for an instant the old misery stabbed at his heart. How difficult it was to hold the eyes fastened on that far horizon when this world lay in the foreground so compelling in its splendour and its strength! (p.15)

For others, however, like the MP for Croydon, Oliver Brand, this banishment of the Divine is a marvel and a delight:

He stood a moment or two at the door after his wife had gone, drinking in reassurance from that glorious vision of solid sense that spread itself before his eyes: the endless house-roofs; the high glass vaults of the public baths and gymnasiums; the pinnacled schools where Citizenship was taught each morning; the spider-like cranes and scaffoldings that rose here and there; and even the few pricking spires did not concern him. There is stretched away into the grey haze of London, really beautiful, this vast hive of men and women who had learnt at last the primary lesson of the gospel that there was no God but man, no priest but the politician, no prophet but the schoolmaster. (p.28)

Set against this ‘vision of solid sense’ is an urban environment which, spiritually and materially, stands at the antipodes of Brand’s London. This is - where else? - Rome …

… an extraordinary city, said antiquarians - the one living example of the old days. Here were to be seen the ancient inconveniences, the insanitary horrors, the incarnation of a world given over to dreaming. The old Church pomp was back too; the cardinals drove again in gilt coaches; the Pope rode on his white mule; the Blessed Sacrament went through the ill-smelling streets with the sound of bells and the light of lanterns … Yet Percy, even in the glimpses he had had in the streets as he drove from the valour station outside the People’s Gate, of the old peasant dresses, the blue and red-fringed wine carts, the cabbage-strewn gutters, the wet clothes flapping on strings, the mules and horses - strange though these were, he had found them a refreshment. It had seemed to remind him that man was human, and not divine, as the rest of the world proclaimed - human, and therefore careless and individualistic; human, and therefore occupied with interests other than those of speed, cleanliness, and precision. (pp.129-30)

What Benson gives us is a dramatisation of the conflict between the ‘two cities’ described by St. Augustine in City of God. ‘On the one side,’ as Augustine writes in Book XV, Chapter I, ‘are those who live according to man; on the other those who live according to God … two cities or two human societies, the destiny of one being an eternal Kingdom under God, while the door of the other is eternal punishment with the Devil.’

These competing visions co-exist uneasily but relatively peacefully throughout the first half of Lord of the World. What changes the game is the rise to power of Julian Felsenburgh, a highly competent, outstandingly intelligent, and seemingly wholly benevolent American, who appears out of nowhere and single-handedly, through his linguistic gifts and his innate diplomacy and tact, saves the world from the prospect of an unimaginably horrific war. He is, we might say, the human embodiment of the built environment and the philosophy behind it which Oliver Brand finds so meaningful and significant. His advent gives the materialist understanding of life flesh and blood actuality. Felsenburgh is not only a symbol of humanism; he is its incarnation and physical representation. Et verbum caro factum est. The Word was made flesh (John 1:14), but this time in an antithetical, genuinely anti-Christian sense.

The smooth, frictionless world that rationalism has built has been reprieved from the depredations of war. The relief is tangible and a kind of mass formation psychosis takes hold across the globe. ‘Felsenburgh’, for instance, is the last word uttered by an old man on his death bed in London, while others kneel down on the pavement before an image of their saviour in a shop window. The religious impulse which, as Benedict XVI well knew, can never be obliterated, because it is part and parcel of who we are, is diverted from the true God, who can barely be accessed any more in this über-materialist milieu, and chanelled towards Felsenburgh instead:

She did not even know at what point her senses told her that this was Felsenburgh. She seemed to have known it even before he entered, and she watched Him as in complete silence He came deliberately up the red carpet, superbly alone, rising a step or two at the entrance of the choir, passing on and up before her. He was in His English judicial dress of scarlet and black, but she scarcely noticed it. For her, too, no one else existed but He; this vast assemblage was gone, poised and transfigured in one vi- brating atmosphere of an immense human emotion. There was no one, anywhere, but Julian Felsenburgh. Peace and light burned like a glory about Him. (p.240)

The key scriptural passage to meditate on here is from St. Paul’s Second Letter to the Thessalonians and is concerned with the Restrainer - ‘he who now restrains’ (Katehon in Greek) - and his antithesis, ‘the man of lawlessness’, who takes centre stage once this Restrainer ‘is out of the way’:

Now concerning the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our assembling to meet him, we beg you, brethren, not to be quickly shaken in mind or excited, either by spirit or by word, or by letter purporting to be from us, to the effect that the day of the Lord has come. Let no one deceive you in any way; for that day will not come, unless the rebellion comes first, and the man of lawlessness is revealed, the son of perdition, who opposes and exalts himself against every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, proclaiming himself to be God. Do you not remember that when I was still with you I told you this? And you know what is restraining him now so that he may be revealed in his time. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work; only he who now restrains it will do so until he is out of the way. And then the lawless one will be revealed, and the Lord Jesus will slay him with the breath of his mouth and destroy him by his appearing and his coming. The coming of the lawless one by the activity of Satan will be with all power and with pretended signs and wonders, and with all wicked deception for those who are to perish, because they refused to love the truth and so be saved. Therefore God sends upon them a strong delusion, to make them believe what is false, so that all may be condemned who did not believe the truth but had pleasure in unrighteousness. (2 Thessalonians 2: 1-12)

The Wikipedia article on the word Katehon succinctly describes how this term has tended to be employed:

The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions consider that the Antichrist will come at the End of the World. The Katehon - what restrains his coming - was someone or something that was known to the Thessalonians and active in their time: ‘You know what is restraining’ (2:6). As the Catholic New American Bible states: ‘Traditionally, 2 Thes 2:6 has been applied to the Roman Empire and 2 Thes 2:7 to the Roman Emperor [...] as bulwarks holding back chaos (cf Romans 13:1-7). However, some understand the Katehon as the Grand Monarch or a new Orthodox Emperor, and some as the rebirth of the Holy Roman Empire. Other scholars suggest that the Katehon is the Holy Spirit or the Church.

It is worth considering, in this respect, that it is only relatively recently that we have been able to categorically state that there is no Roman Emperor or successor to the Emperor active in the world. As late as 1955 there was a Prayer for the Roman Emperor still extant in the Catholic Missal. The Western Empire ceased to exist as a political entity in 476 AD but the Imperial idea lived on and took flesh again with the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor of the West in Rome on Christmas Day 800. The Holy Roman Empire, which he inaugurated, continued until its dissolution by Napoleon in 1806. The Roman lineage in the West, after this, was borne by the Austro-Hungarian Emperors, until the reluctant abdication of the last of these, Blessed Karl of Austria, in 1918.

A similar story can be told in the East, with the Byzantine Empire surviving from the foundation of Constantinople by Constantine I in 330 until the city’s capture by the Ottomans in 1453. This was when Moscow became ‘the third Rome’, with the Tsars assuming the legacy and mantle of ancient Rome (the first Rome) and of Byzantium (the second Rome). That all came to an end in 1918 as well with the savage murder of Nicholas II and the Royal Family by the Bolsheviks at Ekaterinburg.

The absence of the Emperor leaves a gaping void. As Valentin Tomberg notes:

Europe is haunted by the shadow of the Emperor. One senses his absence just as vividly as in former times one sensed his presence. Because the emptiness of the wound speaks, that which we miss knows how to make us sense it.2

It is a void which is aching to be filled, and there is every chance given the way things are going that it will be filled by a Felsenburgh-type figure. The absence of the sacred in our civic and collective lives - already a practical reality - will thus become codified and enshrined in law. The mesh of the secular will then appear complete and foolproof. There will be no way out and no way through, except for the fact that men like Benedict had long ago predicted this and seen beyond the materialist grid that in those coming days will hem us in so tightly that even sensing God’s absence - never mind praying or calling on His name - will seem incongruous and bizarre. But the situation, despite its grimness - or maybe because of it - is far from hopeless. Quite the reverse. As John Waters flags up in this outstanding tribute:

In a series of radio talks delivered in 1969, when he was a youngish professor of theology in Ragensburg, Joseph Ratzinger had spoken of the future of the Church as a marginal, slimmed-down operation, with far fewer members and churches — ignored, humiliated and resented, socially irrelevant, starting over. He predicted that this Church would survive and, in its marginality, become stronger and more vital, but along the way would suffer many trials. The lecture was delivered at a moment of unparalleled turmoil in the Church and in European society — post Vatican II, in the immediate wake of the student uprisings of ’68, Ratzinger had already begun his chosen exile from the centre of Church affairs … ‘We are,’ he said, ‘at a turning point in the evolution of mankind.’ The Church, he warned, would become smaller and would have to start all over again. ‘It will no longer have use of the structures it built in the years of prosperity. The reduction of the number of faithful will lead it to lose an important part of its social privileges … It will be a more spiritual Church, and will not claim a political mandate, flirting with the Right one minute and the Left the next. It will be poor and will become the Church of the destitute.’ This process, he predicted, would last a long time. ‘But when all the suffering is past, a great power will emerge from a more simple and spiritual Church.’ This moment would come when the people on the outside arrived at the realisation that, having lost sight of God, they were living in a world of ‘indescribable solitude’, would come to recognise ‘the horror of their poverty’ and to see the ‘small flock of the faithful’ as something completely new. ‘They will see it as a source of hope for themselves, the answer they had always secretly been searching for.’

We are the people on the outside. It is a good description of where we are now, all the time as a civilisation and far too often in our individual lives. But because we are created by God, there is an orientation to the Divine hard-wired into us, pointing us continually towards reality and truth. Eventually, this innate homing instinct will guide us home to God, our ultimate ground and source. It might indeed take a long time, and given how far we are sunk in rationalism, scientism and post-1968 decay, it probably will. But we will get there in the end and we will know what home is like as soon as we set foot on its soil. The words of Jewel the Unicorn, when he reaches Aslan’s country at the end of Lewis’s The Last Battle, will then be ours:

‘I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now.’3

Pope Benedict believed this too and lived it out in his life and works. His overarching message, despite his pessimism for the immediate future, is radiant and shining. Waters again:

‘The first reason for my hope’, Benedict says, ‘consists in the fact that the desire for God, the search for God, is profoundly inscribed into each human soul and cannot disappear. Certainly we can forget God for a time, lay Him aside and concern ourselves with other things. But God never disappears. Saint Augustine's words are true: We men are restless until we have found God. This restlessness also exists today, and is an expression of the hope that man may, ever and anew, even today, start to journey … The facts confirm this in a single phrase: Deep foundations. That is Christianity; it is true and the truth always has a future.’

Felsenburgh, in Lord of the World, sees the threat presented by the likes of Benedict and Jewel, those who can neither be sated nor deceived by his flat, horizontal, anti-sacred set up. He moves to stamp them out. Like all the great tyrants - past, present and future - he has a mania for total control. But now we arrive at an enticing possibility. What if God gets there first? What if our prayers and acts of charity hit the mark and He throws us a surprise, turns things on their head, and, against all odds, offers us one more era of grace, peace and civilisational renewal?

Sounds unlikely, I know, but this is what has been predicted by some of the holiest men and women ever to walk God’s earth. A new Katehon will flash forth like the bolt of lightning that struck the dome of St. Peter’s on the evening of Benedict’s resignation.

Enter the Grand Monarch.

Meditations on the Tarot (Element Books, 1985), p.86.

C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle (Puffin Books, 1978), p.155.

I was listening to a podcast on Fatima and the strong insinuation that Pope JP II's death, foretold by Lucia, by assassination was prevented by the prayers and penance of the faithful. It's such an antidote to the helplessness the world shoves on us, that our God invites us to change the course of history.

"What if God gets there first?"...."What if", indeed - this is something I've believed for over ten years now...

What if, the 'End Times' don't have to play out as Biblically prophesied? What if those prophecies were intended to tell us what happens 'if we don't pray for God's intervention'?

Maybe all it takes to get a Miracle, is enough believers praying for one?

Another excellent essay, John - God Bless you!